Teaching “One-Off” Classes

An Informational Blog about the Post-Performance Careers of Professional Dancers

The other day I went to the Joyce Theater to watch the New York debut of Dimensions Dance Theatre. While waiting for the curtain to rise, a friend and I were chatting about the fact that I used to know dozens of dancers across nearly every American ballet company. The rosters of companies looked more like a personal year book with a collections of friends from summer intensives, year-round finishing programs, and companies. Today, most of those peers are in the age range of 30-38 years old. In pondering this part of my history, I noted how much things had changed in a short period of time. Nearly everyone who is still dancing are now Soloists and Principals in their respective companies or have left bigger company jobs to dance with smaller ones similar to Dimensions Dance Theatre. One of the most widely known facts is that dancers have relatively short careers. The top inquiry I field regularly in conversation questions the exact age dancers take their final bows. I’ve put a lot of thought into this over the years. So, why not share this retirement chart that I’ve developed and offer some insight to those of you with this common question.

Let me preface this chart with a few things. One of the best pieces of advice that I overheard after a colleague became injured was that there is no timeline to a dance career. I agree with this statement strongly. This is simply my generalized assessment of career duration based off of my own experience and direct research.

The Whole Pool of Dancers (any child that has ever taken class): A great majority of the American female population takes recreational dance classes by the age of 8. Out of this massive pool of dancers very few continue beyond their elementary school years. My assumption is that this is due to lack of interest, curiosity about other activities, financial circumstances of families, and more. I do not believe that many of those who stop dancing do so due to injury.

Middle School Age Dancers: A great deal changes during the middle school years. Aside from the obvious body changes that take place, dancers tend to grow greater interest in social activities with their peers. The next large majority of dancers leave dance during these years. I believe this is due to curiosity about other activities outside of dance (especially if friends are involved), revelations that their changing bodies do not fit certain dance aesthetics, and increased interest in social events. It is also around this age when dancers interested in a performance career will require a greater commitment to classes. Instead of a once or twice a week after school activity, dancers with career hopes will need to be in class 4-6 days/week and commit to longer hours in the studio.

High School Age Dancers: There are many changes for dancers during their high school years. The early years often mimic the end of middle school with some dancers still growing into their bodies and stress over focusing wholly on dance vs. exploring other interests. By the time a dancer is 16-17 years old, they must strongly consider whether they will fully commit to an attempt at “making it,” go to college before pursuing a performance career, or quit and focus on their academic studies. A very small group will choose to continue forward to a finishing school to complete their training with hopes of gaining professional employment. A majority of the rest in the ballet world will end their dance training here. In other genres of dance (modern/musical theatre/commercial styles), it is more common for dancers to attend college before considering professional employment.

Finishing School: Only about 25-50% of dancers who attend finishing school are likely to achieve a professional career. During these final years of training, dancers are pushed to their limit with a multitude of classes, school rehearsals, and (sometimes) company rehearsals. Most dancers need to move away from home as teens to attend. So, they must begin managing how to live, eat, and socialize on their own. Items that can pull this final stretch of training off track include injury (often chronic), disordered eating, lack of balance between work and social life, disappointment (class placement, casting, audition rejections), realization of potential, and more. This and the first two years of a performance career are probably the most difficult periods when it comes to sustaining a dance career.

First Few Years as a Professional: At least 25% of dancers who make it into companies will retire within the first few years of their professional career. Many arrive in a company and think that the success they had throughout their training will automatically roll over to their new positions. But the first few years in a company are a tricky minefield. Most who obtain a career enjoyed dancing leading roles in school performances. When these dancers arrive in a company and are relegated to the back of the studio as an understudy, perform mostly walk on roles in full length ballets, or only receive opportunities to perform dancing roles in the 2nd or 3rd cast of ballets, it isn’t uncommon for dancers to lose interest. Additionally, many dancers sacrifice their social lives during the final few years of their training, only to realize that they have been missing out. Sometimes, dancers will attempt to rectify this imbalance. This can result in loss of interest in dance, loss of focus on work, or too much partying. Also, the mental stress of being responsible for one’s own product and the physical stress of an entire work day dancing can often lead to burn out and injury. For this reason, there is a rather large number of dancers who only get to enjoy 1-3 years of their professional career before retiring and moving into a different field.

Mid 20’s: I’ve noticed that the next cohort of dancers usually retire around the age of 24-27. If a dancer is able to adapt to company life, they usually have a good 5-6 years before they suffer their first major injury. We all have minor injuries on a regular basis, from muscle strains to tweaked ankles, sore backs, and more. But the first major injury dancers have often requires more than a month of recovery or surgery. When this happens, dancers return without the knowledge and maturity to build back into their dancing. Many dancers, fearful that they may lose their jobs, get back to work too quickly and end up re-injuring themselves. Often this second injury causes directors to question a dancer’s ability to perform their job duties (leading to non-reengagement of contracts) or a dancer becomes frustrated and chooses to move on from their performance career.

Early 30’s: A majority of the dancers who retire at this age are long-time corps de ballet dancers who were able to sustain their career, but never had the privilege of promotion into higher ranks of companies. Dancing in the corps de ballets puts the greatest amount of stress on a dancer’s body, especially dancers who also get to perform soloist and leading roles. The body can only take so much. So, it makes sense that a corps dancer’s body is likely to give out before a Soloist or Principal (who may dance more demanding roles, but is usually given more time to recuperate). Additional factors that contribute to this group retiring also include frustration with lack of advancement, directors needing to free up funds for less experienced/less expensive dancers, aging out of roles like peasants, and more.

Mid 30’s: The next cohort of dancers who retire tend to be Soloists. These dancers don’t have the demands of dancing corps roles, so their bodies last longer. Many dancers really begin to complain about recurring injuries and constant aches during their mid-30’s. This age group also seems to feel very fulfilled with the amount of time that they have been dancing professionally. Most soloists appear to hang up their slippers before their bodies completely falls apart.

Principal Dancers: Based purely on my own experience, Principal dancers tend to dance until their body can no longer continue to dance at the high level their rank requires. It is very rare for a director to force a leading dancer to retire. So, it is usually up to the Principal to create a valid timeline as their body and technique begin to falter. Men tend to retire in their late 30’s because their backs can’t handle the load of partnering much further beyond this age. For women, especially those with natural physical facility, it isn’t uncommon to dance into their early 40’s.

Modern Dancers: It seems that the only dancers who completely defy the stressors of an aging body are those who perform works in the genre of modern dance. I have seen professional modern dancers working from the age of 15 to 74 years old. Modern dance has a more realistic progression of roles for dancers of all ages, so it isn’t wildly uncommon to see mature dancers continuing to find artistic fulfillment well into middle age and beyond.

Over the past few months, I’ve been lucky to see a lot of dance in New York City. I had the privilege of seeing American Ballet Theatre in their production of Firebird/AFTERRITE last Saturday. My husband really wanted to see Misty Copeland perform (and often jokes that they are related because they are both from the Los Angeles area and his mother’s maiden name is Copeland) and I was curious to see Wayne McGregor’s interpretation of my favorite Stravinsky score. After the performance was over, I left satisfied with the evening, even though I didn’t love either of the works on the program. It’s been a few years since I left my performance career. But I find that I still experience a range of emotions that likely have something to do with the conclusion of my time onstage.

As any of you who followed my Life of a Freelance Dancer blog know, I didn’t have a straightforward retirement from the stage. I didn’t choose my end date. I wasn’t working with a company that could have asked me to retire or chosen not to renew my contract. I was dealing with a severe injury and burn out, but wasn’t convinced that my performance career would end because of this situation. It took me a few years to find my way to the other side and there was absolutely no denouement when the decision was made. Due to my odd transit offstage, I have had a unique evolution over the past few years when it comes to watching dance performances.

During the period that I mourned the loss of my stage career, I didn’t see much live dance. My freelance career had left my finances in shambles and I was traveling a great deal for work. Most of the dance I experienced was on television. I used to drink glass after glass of wine watching So You Think You Can Dance pondering with my husband whether I should have auditioned for the show when I had been age-eligible. The next morning never made me feel as hopeful as I did on these wine drenched nights. Another dance production I was excited to watch was when PBS aired the School of American Ballet workshop back in 2014. Being an alumni of the school, I was looking forward to reminiscing about my time at this famed institution while watching ballets that I loved and had danced during my career. But a nostalgic evening quickly turned tragic as I internalized what it felt like to dance these works. I shed no tears. But by the 2nd act, I was a grumpy, morose wreck that nobody could console. Here and there, I would see a live performance, usually comped by friends in Pennsylvania Ballet or New York City Ballet. But I had trouble enjoying the art form that was every part of my being. It was just too painful for me to experience because I wanted to be onstage.

During the period that I mourned the loss of my stage career, I didn’t see much live dance. My freelance career had left my finances in shambles and I was traveling a great deal for work. Most of the dance I experienced was on television. I used to drink glass after glass of wine watching So You Think You Can Dance pondering with my husband whether I should have auditioned for the show when I had been age-eligible. The next morning never made me feel as hopeful as I did on these wine drenched nights. Another dance production I was excited to watch was when PBS aired the School of American Ballet workshop back in 2014. Being an alumni of the school, I was looking forward to reminiscing about my time at this famed institution while watching ballets that I loved and had danced during my career. But a nostalgic evening quickly turned tragic as I internalized what it felt like to dance these works. I shed no tears. But by the 2nd act, I was a grumpy, morose wreck that nobody could console. Here and there, I would see a live performance, usually comped by friends in Pennsylvania Ballet or New York City Ballet. But I had trouble enjoying the art form that was every part of my being. It was just too painful for me to experience because I wanted to be onstage.

As I got some distance from my stage days, some pain over the death of my career began to fade. It became easier to watch dance without feeling like I belonged onstage. But while I didn’t want to be up there, my inner critique became overly acute. My husband and I would watch a performance and he would often wonder if we saw them same show. He would love the show and I would have nothing positive to say about it. I spent a couple of years in this stage watching dance post-career. I was overly critical of everything I saw and was quick to compare every dancer to my peers in top-ranked American companies. It was almost like I was experiencing the anger stage of grief. To my husband, it appeared that I was unhappy with anything I saw. And while I wasn’t outraged, I couldn’t find enjoyment in the productions that once gave me life.

The next stage of watching dance in the post-mortem of my career was more romantic. When I would watch shows during this short period, I might as well have been singing the famous A Chorus Line lyrics, “Everything was Beautiful at the Ballet.” This happened during the first few months after I moved to New York once I had the time and expendable income to start watching dance regularly again. I had finally gotten to a place emotionally where I remembered what it felt like when I first fell in love with ballet. I was far enough away from the time that I wished I was still onstage and no longer felt the pain of unmet dreams and expectations that every dancer has when they finish their careers. I also started to realize that enjoying a dance performance wasn’t about tearing people down, most who were just like me. It was actually about being inspired and celebrating the achievements of people in my field.

I think I’ve finally come through to the final stage of watching dance as a retired dancer. Since I am still very involved in the dance world as an educator and choreographer, I find myself happily in the middle of all of the things I mentioned above. I miss being onstage, but I don’t want to be onstage. I am still very critical of what I see. But I look at my criticism from the standpoint of assessing where a dancer is on the timeline of their career and hoping for maximum growth. I only wish the best, even if I feel they need work. And just because I am critical about a performance doesn’t mean that I didn’t enjoy it. I enjoy nearly every production that I see. In fact, I use my opinions and critiques as a tool to improve my own choreographic work and to better develop the range of students I teach.

During certain stages of viewing dance in my post-performance career, I feared that I was beginning to fall out of love with ballet. But this is just another aspect of the fact that “A dancer dies two deaths.” Standing in front of thousands of eager audience members and laying your sweat and soul on the stage is a special thing. To watch others do the same and not have that outlet anymore can test the best of us. There is light at the end of the tunnel. And I find that most former dancers walk a similar path and find their way back. Though, we are no longer the ones standing under the light, we sit eagerly in our seats as the house dims and enjoy the memories of what we once had and the talents of those who followed us.

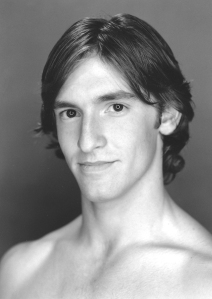

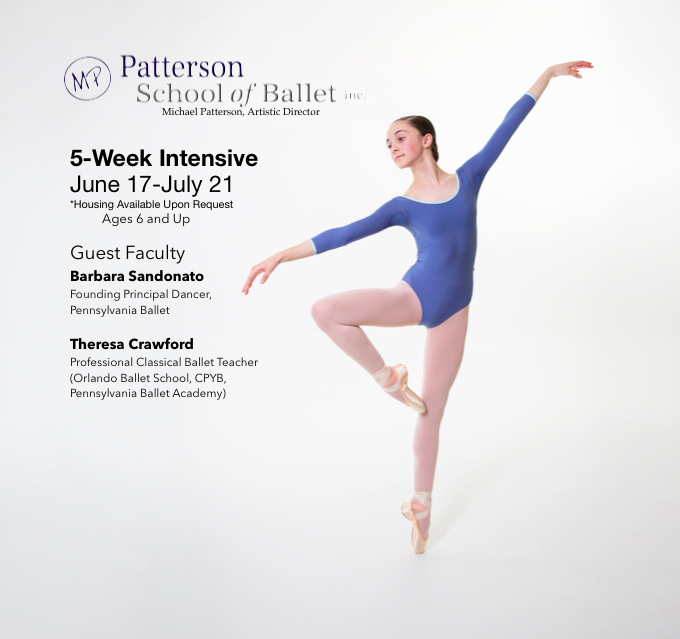

One of my goals in creating this blog is not only to share my own stories and experiences as I navigate my post-performance career, but to also offer a platform for my peers to discuss what life is like after they have stepped off the stage. My first guest blogger for Dancing Offstage is Michael Patterson, Artistic Director of Patterson School of Ballet. I met Michael while he was teaching in the Philadelphia area and have followed him as he moved to Erie, PA, eventually opening his own school. Read on to hear his story and the challenges he has faced as he traverses his second career in dance. Enjoy!

There are many roads to opening and operating a pre-professional ballet school. This is my story. Every story starts somewhere and mine began in Titusville, PA on my family’s dairy farm.

Titusville’s claim to fame is Edwin L. Drake who is credited with the start of the oil industry and football’s John Heisman. Had it not been for PBS, I never would have known that ballet even existed; there were no dance studios in Titusville. No one that I knew had ever seen a ballet before. But at the age of 6, my sister and I were watching our local PBS station and The Nutcracker came on starring Gelsey Kirkland and Mikhail Baryshnikov. I remember being totally mesmerized by their grace and strength and we were glued to the television throughout the duration of the program. I told my mom shortly thereafter that I wanted to take ballet. Her response was, “if that’s what you want to do,” and she went back to work.

At the age of 11, after losing interest in other activities (including baseball, soccer, and piano lessons), I approached my mom and again asked if I could take ballet. This time she signed me up for classes with my sister at Cathy Turner’s Dance Studio in nearby Franklin, PA. It wasn’t until I was 12, at the recommendation of my teacher, that I began studying classical ballet under the direction of Sharon Filone in Erie, PA. Later, I studied at the Central Pennsylvania Youth Ballet under the direction of Marcia Dale Weary and then joined Pennsylvania Ballet in 2002.

While dancing with this company, I was given many opportunities to perform lead roles and toured internationally (with Edinburgh International Arts Festival in Scotland being a highlight). Though I was progressing within the company, I was battling an injury that wouldn’t heal, even with time off. It was at this point that I left Pennsylvania Ballet and began teaching for the legendary American ballerina, Barbara Sandonato, whose daughter I had danced with in the company.

Though I had taught at summer programs on lay-offs, this was my first experience teaching in a school where I was responsible for the long-term training of students. It was also here where I got a crash course in dealing with parents, staging choreography, and setting schedules. With Ms. Sandonato’s guidance, I was able to feel more comfortable in a classroom setting, as well as honing my abilities to produce results and mentor aspiring students. In 2013, I was approached by a local university back in Erie, PA to head their children’s dance program. This new proposition would also serve as an opportunity for me to resume my college education.

When I arrived in Erie, there were only three students enrolled in the program I was to head. In order to promote the school, I dropped off flyers at many of the local businesses and by mid-year had 12 students in my classes. The program was nearly self-sustaining when it was cut only nine months later due to an unforeseen financial situation at the university. I had already planned a summer intensive that had enrolled 20 students, and I was crushed. It was at this time that a family whose daughter was returning to the area (after many injuries at another school) asked if I was interested in starting a school. At the conclusion of my intensive, I decided to meet with a lawyer who helped me incorporate my own school. The Patterson School of Ballet was born on August 18, 2014.

In seeking a home for my school, I looked at many places. But due to financial constraints, I couldn’t afford to renovate a brand new space. As luck would have it, and with some persistence, I found a former yoga studio that was already equipped with a cushioned floor, mirrors, and had been modeled in a way that befit a dance school. The interior was a warm inviting atmosphere, reminiscent of a lodge, and didn’t have the clinical feel that most studios have. I wanted a studio where moms and dads would feel comfortable and guest teachers would feel welcomed. Also adding to the warmth of the studio was a gas fireplace, which is great for Erie winters, and double doors that can open during the summers to allow the warm lake breeze to pass through the studio.

There are many challenges in having a small business, especially a ballet school in Erie. First, the community is inundated with dance schools. I set out to make something different in our community using lessons instilled in me as a child . . . “jack of all trades, master of nothing.” Our students learn how to master classical ballet technique, which gives them the ability to evaluate other dance forms and learn them much more quickly. While they continue to make strides in their classical education, many of the students attend high schools in the area that offer other forms of dance as an alternative to their physical education requirements. So, our students still have the benefit of being exposed to other dance forms. As I mentioned previously, affordability prevented me from building the ideal studio I dreamt of right away. As the Patterson School of Ballet has grown, we recently held a successful fundraiser to raise enough money to build sprung floors in our studio, which will be much better for the long-term health of my students.

When it came to scheduling our Fall classes for the first time, there were many factors that were also challenging. Our greatest challenge was the limitation on evening class times for students. It was difficult to keep up with the numerous school districts, as well as private schools, so I spoke with many parents about class times that would be convenient for them. It was important for me to have my students take the necessary number of ballet classes that a serious program requires. Another aspect that was crucial to the success of the program was finding a pricing scale that was competitive with surrounding studios. Most studios in our area charge very little for classes, with most charging as little as $10/hour. The Patterson School of Ballet’s tuition begins at $10/hour, but as students take more classes the price drops so students that are taking 14 hours of class have an hourly rate that’s under $6/hour. Unlike other studios in our area, our program is all-inclusive, meaning that students have regular guest/master teachers at no additional cost and there are no costume, rehearsal, or performance fees associated with our program. Any rehearsals are in addition to class time, so as to not take away from the purpose of our pre-professional training curriculum. As they say, you get what you pay for. At Patterson School of Ballet, parents make an investment in their training, without ending up with a closet full of costumes.

The Patterson School of Ballet’s curriculum is unique to the area, as we keep small class sizes and a proven graded-level ballet syllabus. Our program offers superior training, but also provides many performance opportunities. Since our first summer program, Patterson School of Ballet has established a 5-week intensive, a super hero half-day camp, and an August intensive. We have had guest faculty and master teachers Theresa Crawford, Matthew Carter, Abigail Mentzer, Melissa Gelfin, Danae Patterson, Frank Galvez, Catherine Gurr, Halle Sherman, Bob Vicary, Elysa Hotchkiss Walls, and Barbara Sandonato (who serves as Artistic Advisor to our school). Our students have had the opportunity to watch company class with Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre, Pennsylvania Ballet, and the Joffrey Ballet, and have seen performances by them on numerous occasions. Our students also regularly participate in enrichment programs provided by Ballet In The City, where they’ve had the opportunity to work with Sonia Rodriguez, Francis Veyette, Lauren Fadeley Veyette, and other fabulous teachers. Performances include outreach with local non-profits in our area, in addition to our year end June Show. This year’s showcase will include Act II of Swan Lake with guest artists Catherine Gurr and Logan Martin.

It can be hard to deal with the competitive nature of having a business in the local dance community. But at the end of the day, I wouldn’t give up my school. While there are many in our community who are incredibly supportive, unfortunately, there are always those from other local organizations that will do or say anything to discredit you personally and professionally. However, it is very important for me to not let that enter in through the doors of my studio. Although the students are not my children, I do have a responsibility to mentor them and help them become the best version of themselves, both inside and outside the studio. My mission is to enrich children’s lives and provide opportunities for personal growth and achievement by utilizing the skills developed in the studio. Any program should be an investment in a child’s future. It is not only our goal to train professional dancers, but to also give students a clear understanding of what it takes to be good at something, to take pride in knowing that you do it well, and to aspire to be more.

Check out more about Patterson School of Ballet at www.pattersonschoolofballet.com

1. I opened a credit card and put nearly $2500 on it at the age of 19 to join Houston Ballet. At the time, my family didn’t have the means to support me financially. So, I used this line of credit to purchase my airfare, put down a security deposit for my apartment, pay my first months rent, purchase a cheap, uncomfortable futon to give me a place to sleep and sit, get cable/internet for communication and entertainment, and stock my fridge.

2. I wasn’t initially planning on becoming a ballet dancer. At first, I saw myself having a career in jazz, musical theatre, and modern dance. After attending his master class workshop in the Philadelphia area, Bob Rizzo (former NYU professor, Steps on Broadway faculty, and current owner of Riz-Biz productions) took me under his wing and generously mentored me for 3 years towards a career in musical theatre. At the age of 16, I fell in love with ballet hard, which quickly changed my focus and the trajectory of my career.

3. While I danced throughout my childhood, my first artistic love was classical music. I started playing piano when I was 5 years old. By middle school, I added mallet percussion (xylophone/bells/vibraphone), flute, clarinet, and saxophone to my repertoire. In my free time, I would record myself playing one part of a duet on a cassette recorder and play it back so that I could practice duets with myself. Additionally, I used to transcribe music on the fly during band practices at school from different keys (for example, playing flute music on the saxophone). At my peak, I could play major classical tunes just by listening to them. When I was in 9th grade, my music instructor called my mom and suggested she send me away to a conservatory for music. I didn’t find this out until about a year ago in a passing conversation on the phone with my mom. I guess she felt I needed to focus on dance at the time. As an adult, I have unfortunately lost some of my skills due to 6 years traveling and focusing on my dance career.

4. I was severely asthmatic as a kid. I had my first asthma attack at the age of 3, which was so severe that I passed out in the car on the way to the hospital. By the age of 16, I was hospitalized 16 times for separate attacks. I only stopped using my in-home nebulizer, 2 inhalers, and pill medication after having nasal surgery in my mid-20’s to clear up scar tissue, congestion, and fix my septum. I attribute both this surgery, playing wind instruments, and dancing every day to relieving my asthma symptoms. Today, I only have to use my nebulizer or inhaler when I’m sick.

5. I have always been very lucky to be surrounded by people who have generously supported and mentored me throughout my career. The famed American Ballet Theatre Prima Ballerina Assoluta Cynthia Gregory was one of my main mentors from the age of 16 throughout much of my early career. She helped guide my decision-making without ever telling me what to do as I entered my career and provided valuable insight as I found my footing in the professional world. I also had the generous support of Daniel Baudendistel during my final years of training with private instruction in pas de deux, as well as him providing me with private instruction with the legendary David Howard. Also, as I mentioned previously, Bob Rizzo was a great guiding force in my teenage years as I really sunk my teeth into the idea of a career and life in the dance world.

6. Alaska is practically my second home. Back in 2012, I was first brought out to Anchorage to dance with the now defunct Alaska Dance Theatre professional company. Over the past 6 years, I have spent almost an entire year in the state between professional performance work, directing Alaska Dance Theatre as Interim Artistic Director, and creating my own intensive programs for intermediate/advanced students.

7. A lot of my choreographic work has focused on my fascination with the human psyche. A lot of this (and likely a huge part of my diving into dance training) is due to the fact that I was raised in a house with a parent who had an undiagnosed mental illness. A few years after leaving home, my step father was officially diagnosed with bipolar disorder and depression. While I learned how to cope in an unconventional home throughout my childhood, he wasn’t the only person in my life suffering. As a teen, I helped a few friends cope with mental health situations that could have become potentially life threatening situations. And as an adult, I have found myself in regular contact with people suffering with diseases and disorders from Bipolar to Schizophrenia, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, and depression.

8. When I was finishing up my ballet training, I was concerned that I wasn’t going to be offered a contract to start my career. As a counter to my anxiety, I auditioned for 17 ballet companies. Considering my expectations, it was quite surprising to me when I ended up with offers ranging from Corps de Ballet to Second Company contracts with Houston Ballet, Pennsylvania Ballet, Kansas City Ballet, Colorado Ballet, Carolina Ballet, Alberta Ballet, Oregon Ballet Theatre, and a trial contract with American Ballet Theatre. I was quite lucky that my expectations didn’t match my reality.

The first time I heard anything relating to social media was during my time living in the dormitory at the School of American Ballet. There was a young student, who at 16 years old was using the Myspace network as a sort of coming of age and coming out. Essentially, while I didn’t come to know the term social media for years, my first impression of MySpace was that it was a site used for the sexually promiscuous and for those willing to risk their lives in the process of making bad decisions. It probably makes sense why it took another 2 years and the influence of my first love to get me to join a world that would eventually become an integral part of my (and many others) life.

I reluctantly joined MySpace back in 2003 and, like most any Xennial, quickly adjusted to a life where we shared the thoughts inside our heads with anybody who dares to cross our profiles. It only took me a few weeks to go from lurking to writing short blog posts for my friends and colleagues (at the time, I wouldn’t dare let my family see my profile). As I learned that MySpace wasn’t what would eventually become Tinder or Grindr, I began sharing more and more of my daily experiences and personal thoughts. Just like the judgment of my peer at the School of American Ballet, my colleagues at Pacific Northwest Ballet began to judge my decision to share more of my life publicly, both behind my back and to my face. I remember a moment when a Principal dancer who was most rarely kind or friendly towards me pulled me aside and demanded, point blank, that I needed to stop blogging on my MySpace page. I remember the conversation that followed with my (now) husband, where I told him I felt that it was important that I share my life publicly because it was an expression of myself as an artist and human. In 100 years, they may say I was one of the pioneers of social media. My husband’s response (who is Gen X) was supportive, but also stated the fact that he also would never share his personal life in the same way. We spoke at length that night as I evaluated whether I was going to continue down this path of being as publicly honest and straightforward as I could or whether I was going to carefully guard my life experiences to avoid anybody vengeful using my public sharing against me either professionally or personally.

If you are reading this blog, it is quite clear which decision I made. After some time and over 400 blog posts on MySpace, I transitioned my full energy to Facebook. It took me a few years to start writing in any type of blog format again, but it eventually happened. If you don’t know my story, I’ll share it in brief here. But you should really browse my first blog, Life of a Freelance Dancer, if you want the whole story. While I had become adept at using Facebook, my social media expertise didn’t really become apparent until I began blogging again. I didn’t start up my second blog out of boredom, expression, or curiosity of the reactions of others. Instead, I did it out of fear and necessity. After transitioning away from dancing with a major ballet company to stretch myself as an artist with a small, grassroots contemporary ballet company, I became injured and was eventually fired because of this injury. It was too late for me to get healthy enough to participate in audition season and I couldn’t imagine moving again so soon after relocating my home and family 3,000 miles for the job with this company. I knew I could write, but I didn’t know if people would read anything outside of random musings and thoughts from my days. But I pushed forth and began sharing my experiences and thoughts on Life of a Freelance Dancer as I attempted to salvage a failed attempt to try something new with my career. The first handful of posts, I remember friends reaching out and asking for me to stop sharing my blog on Facebook or they would unfriend me. They felt like I was marketing on a personal platform, kind of in the same vain as a pyramid scheme. I pressed forth anyway, and eventually my blog became so popular that I didn’t have to audition for work, I spent nearly 35-40 week’s on the road dancing yearly, hundreds of people were reading my blog daily in over 120 countries around the world, and I was included on a list of 49 Creative Geniuses Who Use Blogging to Promote Their Art. I didn’t quite realize it was happening because I was living it, but my social media star had risen. I had become a role model for many hopeful freelancers, working professionals, and people looking for inspiration in general. It was nice that I didn’t have to worry too much about what I posted because my audience mostly consisted of adults and students in their late teens who were prepping for a career.

It was thanks to my willingness to offer the most candid presentation of my life and my life’s work that I had achieved all that I had in a short 4 years. After I was featured alongside New York City Ballet Principal Megan Fairchild in the January 2016 issue of Dance Magazine for being an innovator in social media, I was approached by Kimberly Falker of the Premier Dance Network to host my own podcast show on her network and iTunes. Suddenly, I had a massive platform to continue doing something that dancers were never really known for, sharing my voice as a part of my art. My brand is candor and it is daring due to the fact that the dance world doesn’t necessarily function on fact. It can be dangerous to be vocal about the less ideal parts of our art form, like sexual harassment, injury, burn out, anxiety, or emotional training. But my willingness to share my experiences and stories with the dance world and beyond has really pushed me into the spotlight more than I ever was while putting all of my sweat and tears into my performance career.

Now, the point of me sharing all of this information isn’t to create a documented timeline of my social media experience or gloat about my successes that have arisen from being an over-sharer. Instead, I am writing to discuss a challenging topic that I have recently been facing within my personal social media. As my interest in Facebook has steadily declined (mostly due to algorithms, the political mess of 2016, and too much noise instead of personal connection), I have turned more and more of my attention and effort to Instagram. I was quite resistant to join this photo/video sharing network mostly out of fear that it would take up more of my non-existent time. Although I delayed, I knew it was inevitable that I would eventually join this platform and immediately fall in love with this visual app. I’ve always had a knack for taking photos and I love the idea that Instagram offers me the opportunity to show my followers what it looks like to see the world through my eyes. I already had a good following on Facebook and on my Life of a Freelance Dancer blog when I joined. So, I never really felt the need to build an audience of followers beyond my family, friends, colleagues, and peers. That was until my recent falling out of love with Facebook.

As I have transitioned more of my attention to my Instagram (https://www.instagram.com/bkerollis/), I have been slowly gathering followers who enjoy my content and want to follow my career and lifestyle. I feel that I’ve gotten particularly good at cultivating a following within my network just by posting the things that I enjoy and the work that I am doing. These items include dance, city life, skyscrapers, and imagery of my travels. But my wishes to grow a vast audience, brand, and network beyond my daily reach of people I personally interact with has become a challenging conversation that involves who my audience is, what communities I belong to, and my own personal integrity.

For me and my regular brand of candor, I want to post whatever images and content I want to at that moment. But things have changed a lot for me over the past few years. I am no longer backstage dozens upon dozens of time during the year and promoting myself solely as a performing artist. My audience has widened in many ways. I work with students ranging from young hopeful 10 year olds up to recreational 80 year old adults. My audience consists of everybody from small kids to gay men to Broadway dancers, ballet dancers, podcast listeners, blog readers, fans of my photography, parents of my students, and more. As I said earlier, I have been slowly building my Instagram audience. But I now feel ready to go all in to promote my choreography, teaching, and media work to a much larger audience on an international scale. The main challenge here is how does one build an audience with integrity while catering to a range of communities as diverse as my own. I have really struggled with this idea lately and, perhaps, this is the reason that I am ruminating over this publicly. I don’t want to post videos of myself dancing, as I would rather spend my time focusing on making my students into amazing dancers. I already had my performance career. Sometimes, I find it tempting to post practically nude photos of myself to cater to the gay community and gather easy follows. Sex sells and I still have my dancer body, so it could be a cheap sell. But I have children looking at my account, parents monitoring my activities, and being a married man I don’t need to market myself in that way (though I will post the occasional artistic nude-ish photo). I also don’t like to build an audience using hashtags like #followforfollow, as I feel that there is no investment from those followers beyond patting them on the back. I want people who see my content to be invested in what I am doing, sharing, and promoting.

So, at the moment, I am finding myself caught in a social media pickle. How does somebody like me market to a vast audience with differing tastes, receive brand sponsorships, gain opportunities in and out of my field, and add followers who are invested in the work that I am doing? I’m not sure that I really know at the moment. But for anybody else who has found themselves in a similar situation, I can tell you that it is important to set standards for yourself and move forward with integrity. If you have integrity, no matter the outcome, you will always look back and be proud that you didn’t sell out to get ahead. I have chosen to move forward with integrity and am trying to set certain standards in my social media practices. Photographs that include nudity will only be shared if they are artistic and tasteful. Footage of myself dancing my own choreography in a class will only take place if I am regularly posting footage of my actual students dancing it with me, my attention is focused on them for the entirety of the class, and filming doesn’t take place more than once or twice a month. And, lastly, I will build an audience based purely off of people who want to follow me, and not off of some idea of reciprocity where somebody disinterested in my content will follow me only because I have followed them.

With all of this said, I am curious if you have found yourself in this same type of situation. Do you have a wide range of audience members and have trouble making sure that your content is completely appropriate for all of your viewers? What do you think of posts where the teacher is dancing front and center in a class they are supposed to be teaching? Do you believe that you should build your audience and then cultivate content to keep them interested or that you should only seek out followers who found you because they initially liked your content? Feel free to leave a comment here or to reach out to me on Instagram to let me know your thoughts!

There are so many lessons to be learned in this life. In the past few weeks, I spent some time with a handful of my students coaching them while at the Youth America Grand Prix competition. I was so impressed to see how they held their own under the pressures of competition, and a handful of them even placed (one of them won the Grand Prix, two won 2nd & 3rd place in their categories, and a handful placed in the Top 12). While my job was to warm my kids up, hone in their focus, and provide support no matter the outcome of what happened onstage, I learned a very important lesson. Read on to see what that lesson was along with a handful of others I’ve learned since retiring from the stage.

1. One of the most surprising lessons I’ve learned since retiring has been that I don’t have to take class every day to maintain my technique. As my schedule has become overwhelmingly booked with teaching, coaching, choreographing, podcasting, and blogging, I have had difficulty making it to class as often as I would like. But taking class 2-4 times each week (as opposed to 5-6 times) actually allows my body to recover and feel better from day to day. While there are a few areas I feel that I’ve lost ground in (adagio and extended stamina), I can still perform a majority of the feats I executed daily during my stage career. And if something isn’t working one day and it stresses me out in the moment, I just remind myself that I’m retired from the stage and class is now wholly for me again.

2. With no intention for any negative connotation, a performance career is very selfish. In order to perfect one’s art, we must spend countless hours working on ourselves and focusing great attention to personal detail. Beyond this, due to the brevity of our careers, we tend to feel that we need to achieve every goal we set, gain every opportunity available, get cast in every role we dream of, and climb up the promotion ladder as fast as possible. It has been liberating to step outside the selfishness of my own performance career and to allow my focus to include others. In the past few weeks while coaching a handful of students to compete at Youth America Grand Prix , I suddenly became very aware of how invested I was in the success of my students. I was so extremely hopeful for them to perform well because their success and happiness was also mine. This post-career life has taught me that the success of many is greater than the success of one.

3. This may sound odd since my attention has shifted from fully focusing on my own instrument. But my technique has improved greatly since I began teaching and coaching dancers. While teaching my students, I often have to find unique ways to express muscle engagement, joint movement, placement, balance, coordination, and more. I find myself evaluating my own work in class much more meticulously as I explore the best way to convey information to students while teaching. This has netted an overall positive in my own dancing, as I have a greater understanding of many things that I hadn’t grasped during my performance career.

4. I didn’t always notice this, but there were many times that I wish I had a certain type of support, guidance, or mentorship during my career. I left home at the age of 17 to train and I moved across the country into my own apartment at the age of 19 to start my career with Houston Ballet. As I transitioned to Pacific Northwest Ballet, became an adult, and eventually navigated my way through a national career as a traveling freelancer, I often wished that I had more support in many ways. Now that I have stepped into a more educational leadership role, I have been baffled by the number of dancers who have reached out to me in need of physical, emotional, and financial support. If these are the dancers that are asking for help, I can’t imagine the number of dancers who don’t ask. One thing that has become abundantly clear to me is the need for support in our community and the lack of resources, access, and assistance available to help our the real-life culture of our country.

5. Throughout my nearly 13-year performance career, I gave up a great deal to fulfill my life’s biggest dream. From saying no to social events to avoiding activities that had even the slightest risk of injury, traveling for 4 years away from the comfort of my friends and family, and avoiding foods that may add that extra pound of weight onto my body, I sacrificed much to enjoy what I still consider one of the greatest experiences of my life. Now that I am officially retired from the stage, I have been able to enjoy my time in different ways. I now see that there is so much more to life than dance. But that doesn’t mean I love it any less. It is still the focal point of much of my attention. But I don’t limit myself in ways that I used to and I don’t feel like I am missing out as much.

6. While there is often a great deal of competition and comparison throughout a performance career, all former professional dancers share a special bond that connects them once offstage. One of my favorite experiences in recent history came while teaching a master class at Uptown Dance Company in Houston, TX when a former colleague with Houston Ballet took my class. She had been a long-time soloist with the company when I joined as a young apprentice and I looked up to her and respected her time put in. Since I was younger, I remember feeling shy around her. But now that we are both retired and have shared similar career experiences, we shared some good conversation and laughs while reminiscing about our past career lives.

7. When you retire, some aches and pains go away and other aches and pains get worse (The ones that get worse are usually when you are teaching – see previous blog post about this here). But the stress and anxiety that accompanies minor to moderate pain or injury is not nearly as great as when you are preparing to perform.

8. When I was finishing up my career in my early 30’s, I was often considered older for a dancer. By my late 20’s, I already found myself a guiding force for younger dancers entering the field. In fact, at one gig, I was jokingly referred to as Papa Bear. When I finally decided to officially retire at the age of 32, I suddenly became young again. I can’t tell you how many people have mentioned how young I am for a teacher and choreographer at my level, even at the age of 34. It was quite surprising to see how quickly I went from being old to young again. Perhaps, retirement from a performance career is the real fountain of youth.

9. Dancers are the face of our field. But as I have started to experience how I am treated (whether locally or traveling) as a choreographer and dance educator, I have come to see how absolutely undervalued and mistreated dancers are. When I freelanced around the country as a performer, I had to fiercely negotiate a livable wage, deal with questionable housing accommodations, and handle situations in and out of the studio that most professionals in other fields would never find themselves in. Since I have begun working in my post-performance career, I have been treated much more respectfully when it comes to salary, travel, accommodations, and treatment. This is definitely something that I would like to inspire to change in our field. I am still baffled that dancers, the face of our art form, are so often the least valued commodity in dance.

10. I’m actually more in love with dance than I have ever been. I thought that getting to perform my dream roles in my dream companies would be the pinnacle of my love for the art form. But while those experiences were amazing, there was a certain level of stress and anxiety that went hand-in-hand with preparation activities and live performance. Now that I have succeeded in my performance career and have moved on to teach and choreograph, I get to enjoy every part of the dance world that I love, leave the parts that I don’t love behind, and make sure that almost everything I do is for me, because I want to do it, and to share my passion with others.

There aren’t a great deal of guidebooks when it comes to navigating one’s way through many parts of our insular dance world. Over the years, we have made gains with more information and resources to help prepare dancers for auditions, professional life, and retirement. But there is still a dearth of guidance when it comes to finding support for your work as a choreographer and putting yourself out there to gain commissions. While I have had some success when it comes to choreographic workshops and competitions, I am still very much in the navigation phase of coming into my own as a prominent dance maker and gaining commissions to create and present larger scale stage works. When I first started my blogging career on Life of a Freelance Dancer, I was writing to fill a void of information that I wish I had available to me as I navigated my freelance career. Here on Dancing Offstage, I am hoping to do the same thing with the post-performance careers of dancers. So, while I haven’t yet fully achieved my goals as a choreographer, I plan to share what I have learned thus far for those of you who may be seeking content to help kick start your choreographic career.

There is no straight line to gaining work as a dance maker. But there is one clear place that all budding choreographers need to start. Get in the studio and start fine-tuning your craft by making some work. One of the most difficult parts of building a choreographic portfolio rests in getting in the studio to sharpen your creative pencil with quality dancers who can appropriately portray your ideas. As you continue to learn how you work in the front of the studio and refine the process of taking inspiration from your mind and putting it into a physical form on your body and other dancer’s bodies, the next clear step is to record footage of your work. Video of your creativity doesn’t need to be caught by a professional videographer and it doesn’t need to be filmed on a $2,000 camera. But it does need to be clear, far enough away that it doesn’t cut off the full visual effect that you are trying to create, and offer a crisp idea of who you are as an artist. While many workshops and competitions do not require that you have full stage production footage of your works, some do. And almost all commissions from organizations will come from a director who appreciates knowing that you have had the experience of producing a studio work that translates appropriately onstage. So, if you need footage of your work in a theatre format, perhaps consider applying to be a part of festival or ask around your local scene for performance opportunities.

(Click Here to see footage of a recent submission of my choreography)

Now that you have footage of your work, what are you going to need to put in your package, how do you find opportunities, and who do you send it to? Again, there isn’t any perfect answer to these questions. But with a bit of research and a bit of luck, you may find something that is perfect for you. Many choreographers assume that their work will speak for itself. And for a very few people, it may. But behind many of the most successful choreographers is also the mind of a writer, a presenter, and a hustler. Unless a director outright hires you to create a work for their company, most of the potential opportunities that will present themselves will require a proposal. These proposals often ask for a bit of background on oneself, where you find your inspiration for your work, and what you imagine you could make (which would include content of choreography, number of dancers, style of dance, music choices, etc.). Beyond all of this, a proposal is often requested in the form of a letter of intent, which requires you to state why you are applying. There is no exact formula for these letters of intent or proposals, but a bit of research on the company (including general style, number of dancers, etc.), past collaborators, and budget can go a long way in informing you on how to address your proposal. You may also be required to provide one or two letters of recommendation. Beyond all of this information, be sure to have an updated choreographic resumé that notes your professional experience as a dancer (to share your background and qualifications), as a dance maker, and the dates of your previous work. Many workshops will not accept submissions with footage of works that are older than 3-5 years. They want to know what your current work looks like and often have strict standards for submission footage.

While there are some workshops, residencies, and competitions that happen every season, most programs only occur when there is funding or on a less than regular basis. During your search for opportunities, you may find old links to choreographic workshops that claim to happen every other year, but are actually listings from 5-10 years ago. While at other times, you may read about a certain choreographic competition that intends to run annually, yet the organization only puts on the event once. I don’t know the exact reasoning for this, but I imagine that funding is a major factor. Also, some workshops gain financing through grants that have extremely strict qualifications for organizations to receive this money. An example of this is the Joffrey Ballet’s Winning Works competition (formerly Choreographers of Color), who only accepts submissions from non-white dance makers. When seeking out opportunities, be sure to very clearly read all of the information and submission specifications from start to finish before you begin prepping a package to send out to avoid wasting your time due to outdated information or not qualifying for the opportunity.

One of my best choreographic experiences thus far was having the opportunity to create for 3 weeks at the National Choreographers Initiative in Irvine, CA (please read about this experience by clicking here). As I stated previously, if you are non-white, the Winning Works competition at Joffrey Ballet also seems to happen yearly. Other regular opportunities I have seen include the New York Choreographic Institute (very difficult to obtain), Western Michigan University’s Choreography Competition, McCallum Theatre Choreography Festival, UNCSA choreographic development residency, Milwaukee Ballet’s Genesis Competition, SpringBoard Danse Montreal, NW Dance Project/Pretty Creatives, and NYU Center for Ballet and the Arts fellowships. Other than these known opportunities, I am regularly perusing dance periodicals for new listings and checking out Dance/USA, Dance/NYC, and Dancing Opportunities for new listings on choreographic pursuits and funding opportunities. In the end, it never hurts to perform a Google search on “choreography competitions,” “choreography submissions 2018” (or whatever year it is), or “choreographic opportunities.” Lastly, while you can seek out many opportunities by looking online, don’t discount your network of friends and colleagues, as more work presents itself from within your community than from cold calling organizations.

Once I’ve found certain opportunities, I send my package off to the person or form that is denoted on the site. But what if I am specifically seeking choreography commissions with professional organizations? How do I get in contact with the right people with a dance company to make sure that the director gets to see my work and considers me for the future? This is a completely different beast. Taking a page from my freelance career, I have become a master at cold emailing organizations expressing interest in creating work for organizations. I have a template email that I adapt to fit each company that I reach out to. I make sure to do a little research on the company before contacting them and to make sure that they can see that I truly am interested in the company (perhaps by discussing their current season, any tours the company is taking, or discussing something I saw in the news pertaining to the organization). As I get to know certain directors who have expressed interest, my template obviously changes to a true personal email. But this takes some time and a certain track record to achieve. But the best way to reach out to a director is to seek out their email on the company website or call the front desk and request that information, to track down information on the Artistic Director’s direct assistant, or to look for a ballet master, ballet mistress, or company manager who may answer directly to the person in charge. I can tell you from experience that this is a very tedious process that usually gets anywhere from a 10%-20% response rate. But unless you have direct access to speak to an organizational leader, you have to start here.

As you can see, there are many pathways to building a choreographic career without any clear or direct path. Like many things in life, success in dance making is often led by a small pack of choreographers who are talented and have found luck in timing and presentation that gave them a platform to show their ingenuity. I have felt so lucky to be selected for the National Choreographers Initiative, as a finalist at the McCallum Theatre Choreography Festival and Visions Choreographic Competition, and to gain commissions for Columbia Ballet Collaborative, CelloPointe, Uptown Dance Company, and many students competing at Youth America Grand Prix (Click Here for footage of one of my students prepping for YAGP). But my true dream is creating larger scale works for professional organizations around the world. While I am not there quite yet, this is all of the information I have learned along the way to building what I plan to be a very successful choreographic career. I hope that my sharing this information with you is greatly helpful. And I hope that our paths cross as we work towards achieving our dreams!

As professional artists, we have worked very hard to perfect our art. In fact, for many of us, our entire lives have been dedicated to perfectionist acts in order to understand, live, and share our art form. For me, it sometimes feels like there is nothing more important than the refinement process in the studio, the artistic process in the psyche, and the exploratory process in the form of play, trial, and error. But at times, I catch myself sharing my artistic practices (something I care about very deeply) as if they have more value than anything else in the world. I’ve wondered over the years whether this makes me impassioned or gives off an air of pretension.

During my time dancing with Pacific Northwest Ballet, I was extremely unaware of the insular artistic bubble that I existed in. While dancing for this high-end organization for 7 seasons, dozens of highly qualified artists worked diligently daily beside one another using collaboration and competition to boost one another to the next level of perfectionism. This works well on an insular level. But it also tends to dissolve an artist’s reality outside of this bubble, as it requires an intense level of commitment and effort. Striving for perfection daily along with constant peer-to-peer comparison creates an atmosphere of exponential growth. But it also cultivates a sense of judgment that (while helpful and understood within our tight-knit community) bled outside of our thickly insulated bubble. This often led to intense scrutiny of all things across our art form as if they were all being judged by the same standards as we were, albeit not sharing our company history or budget. It took me leaving this intense, safe atmosphere to recognize the benefits and downfalls of having a mentality that the work we were doing was more important than most anything else. This was a place where anybody who wasn’t achieving an equally high standard as we were could be judged using words including bad, fat, unmusical, cheap, awful, weak, unqualified, and a variety of other negative descriptions. While this may appear as perfectionist behavior within one community, it may project as pretentious if these unwelcome opinions are shared.

Every dance artist has to start somewhere. Aside from maybe one or two prodigies in every generation that passes by, practically no dancer naturally begins performing technical exercises with perfection, maintains perfect physical form at all times, dances with immaculate musicality, or exudes the inner soul of every character they portray. Most of us start out with recreational intentions. And many of us do so without regards to how our feet are pointed, how fit we are, or how it makes us feel emotionally. All of these characteristics plus passion must be cultivated within an artist over a period of time without judgment beyond constructive individualized criticism. Similarly, all audiences must be shown why it is important for them to be involved in any cultural institution. If we present artists with expectations of pure perfection before they are ready to put that pressure upon themselves, it will be impossible to build the future of our art form.

In my own personal practice as a dance educator and choreographer, I have found myself exploring the practice of making our art form important to my students without coming off as pretentious about the need for extreme effort, motivation, and artistry. Just because I had success in my performance career and love what I do doesn’t mean that anybody who enters my classroom will share the same sentiment as me. Just because I tell a student that something is important doesn’t mean it actually is to them. What I try to do is slowly educate those in my classes about all aspects of our art form. By adding interesting trivia questions at the beginning of class, I subtly educate students on American (and sometimes international) dance culture. Whether listing off major, regional, and civic dance companies, to explaining the company rankings, offering details on full length and one act works, the internal administrative and artistic workings of a company, and choreographers of note, I offer information that a student can take home with them and research if they find it interesting. Beyond this, I use other tactics to motivate physical and artistic development. Only when we pique a blossoming artist’s interest can dance become something more than an after-school activity.

When I first started teaching, I expected dancers to work hard because I already had them in my classroom. What I found was that many dancers didn’t understand why they had to work hard or know how to work hard in a way that was effective. My perfectionist tendencies would project onto students and come off as pretentious because they had not yet bought into the process or the need to create a sense of importance around their work in the studio. It is necessary to buy-in to do many tasks that artists do. Why do I care that I am holding my leg at or above 90 degrees for 8 counts? Why does it matter if I do or don’t let my standing leg give out in a pirouette. Lately, I have found myself telling students that, in the grand scheme of the world, it isn’t important that they want to do these things. But in order to accomplish these feats, it is integral that in those moments they are working in class or onstage that they feel that the work is the most important thing on earth. Only then can we accomplish superhuman feats. But it is also important while working with impressionable students (young to senior) that we remind them that there is a reality outside of our beautiful art form that must be recognized.

Looking at the separation between pretension and perfection in our art form also lies in who we are interacting with and how we respond to others that we feel haven’t yet obtained the same level of execution or understanding that we have. If something is important to me, but not you, and I really push the point, I may come off as pretentious. We too often share the tendency to tear down others in their process of finding artistic excellence, especially without consideration for where they came from and where they are going. I remember when I first started my 4 years freelancing with multiple established and fledgling professional organizations across the country. Only having the standards that surrounded me during my time dancing at PNB, I judgmentally felt that anything that wasn’t on the level of work that I had been a part of during my tenure there was either bad, dysfunctional, or laughable. I was afraid to share some of what I was doing publicly for fear of humiliation when viewed through the eyes of my former colleagues. But what I learned throughout this period was one of the most important lessons I’ve learned throughout the entirety of my nearly 16 year career, thus far. We must remember that we are not all dancing along parallel tracks of artistic growth and expectation. We all exist in different stages of our art form and all have different purposes that can grow or reroute at any time. A great example of this can be seen in the differences between dance organizations across the country. Some regional dance companies are still in the audience education period of their organization’s growth. Yes, their practices may currently be flawed. Yes, the quality of their performances may pale in comparison to companies with multi-million dollar budgets. But most of the nation’s finest cultural institutions started this way. Look at American Ballet Theatre. When they were merely just Ballet Theatre touring around the country by bus and performing in any and every theatre possible, they probably didn’t have the finest quality productions. Additionally, there was no nationwide comparison to vouch for the quality of these dancers. But look at them today. They are one of the leading arts organizations in the world.

The important thing to recognize here is that all artists are an important part of our community, whatever stage they are at in our art form. And in order to continue cultivating dance into a sustainable place, we must develop the importance of perfectionist actions through a carefully curated process that neither pushes potential artists away from the art form, nor tears down working artists that are not quite as far down their professional path as you are. If a young dancer stops training because the teacher doesn’t slowly allow them to explore why our art form is important, we have failed. If younger arts organizations try to force their audience to understand our art form too quickly, people will look at the organization as if they are pretentious and the company may begin to lose support. Without community support an arts organization can no longer exist. Pretension is a turn off that slows down or completely halts the progress of our art. For this reason, it is so important that we don’t let our own personal or “insular-bubble” perfectionism project unto others. Instead, I find it best to offer a helping hand that is ready to offer guidance and insight only when an artist is ready to accept it.

Some dancers have the luxury of meticulously planning out their retirement from the stage and glissade-ing smoothly into their second career. While this is a reality for a small handful of artists, I have learned that it isn’t for the majority of us. Whether a dancer suffers a sudden career ending injury, gets non-reengaged by their company, or freelance work becomes more of a chore than artistic fulfillment, many dancers don’t get to plan out their retirement strategy with tons of advanced notice. For me, I experienced two completely different realities throughout my career; one that included support to prepare for the future and one that drained nearly half of my life savings and accrued substantial credit card debt in a short few years.

I feel blessed that I was employed for 7 years by a company that invested in its dancers and their futures. Aside from having the most generous 401K match for dance artists in the country (to help make up for the brevity of most dance careers), Pacific Northwest Ballet also encouraged us dancers to partake in a revolutionary program that granted up to $8,000 to each artist in the troupe (which could be used towards a college degree or post-performance career pursuits). During my time with the company, I used grant money from our Second Stage program to take classes at Seattle University, transferred those credits to gain my Associate in the Arts degree at Seattle Central Community College, and purchased equipment to build materials for my budding choreographic career. I was very proud that when I left PNB I had built up a substantial amount of life savings, had deleted all of my debt, and had obtained some level of college education while sustaining a performance career with one of the nation’s most illustrious dance companies. I felt I had gained some important ground on preparing for the future, whatever that meant at the time.

Once I transitioned from big company life to that of a startup contemporary ballet company, things quickly began to unravel. My husband and my cross-country move, a sick cat, a major pay and benefits cut, and a lease at an apartment owned by a slumlord quickly drained the $10,000 I had apportioned into my savings account for moving costs and emergencies. A poorly timed injury and the subsequent fallout (which cost me my job) wiped out the remainder of that hard earned savings within 10 months of moving across coasts. I spent the next 4 years working through feast-or-famine periods as a nationally-touring freelance artist. While on paper this was one of the most fruitful periods of my performance career, it was full of difficulties, stress, and anxiety surrounding my already damaged finances, my physical health (which was difficult to maintain performing with 8-10 different organizations around the country each season), and my emotional health (which suffered from being alone on the road for 8-9 months each year). In 2015, while attempting to recover from my career ending injury (which occurred in 2014), I came to the realization that nagging volatility and pain in my lower back would prevent me from returning to the stage. At this point, I began to consider transitioning into the second stage of my dance career. Only, I didn’t know it would cost me nearly $40,000 and 2 years of effort to fully arrive on the other side.

Most dancers don’t have the means to transition in the way that I did. While I began super-commuting to New York City in order to build my choreographic and teaching portfolio, I had to begin pulling money out of my 401K to survive and completely focus on transitioning. I didn’t have any money left in my savings account and I had begun to slowly accrue debt because I could no longer make money from dancing. Additionally, I had no other work experience outside of my specialized field, therefore any new work would be at greatly reduced rates from what I had developed throughout my adult life. What most dancers don’t realize is that it costs a substantial amount of money to transition appropriately and as quickly as possible. Aside from paying bills and rent, there are other financial items that often arise while transitioning; like the cost of education, reduction in value from previous income, and room for trial-and-error. Dancers who choose to stay in our field as dance educators or choreographers typically drop back to entry level rates of pay, as well. While dancers who choose to try something new have the exorbitant costs of college courses, fitness training programs (like yoga, pilates, or personal training), and a wide array of other financially draining items. The major challenge faced by retiring dancers in paying these additional costs is that most didn’t have expendable income during their careers to save up for these expenses, especially when transitions happen unexpectedly. This often leads dancers to rely on low wage non-career focused work to give them a chance to find their new passion. There is very little sympathy for retiring dancers who paid the price of college tuition during their finishing training years, started their professional careers in their late teens, and became so specialized in such intense atmospheres that there was little room for outside interest or cultivation of potential secondary work passions.

While I hated pulling money out of my life savings, I feel extremely lucky that I had this to fall back on to avoid distractions on my path towards transitioning to choreography, dance education, and media work. For dancers who have no choice but to fund searches for their post-performance careers with non-career trajectory work, they run the risk of slowing down their transition process or completely derailing it just to survive. While nobody should be given a direct hand-out at the end of their stage careers, it is important that companies work to provide dancer’s appropriate support and financial tools to ensure that they can transition safely and appropriately, whether it is their own choice or fate that pulls them away from the stage.

(How did you finance your transition? Did you have to take work that negatively affected your transition or forced you to give up on your hopes for the next step of your career?)