Teaching “One-Off” Classes

An Informational Blog about the Post-Performance Careers of Professional Dancers

The other day I went to the Joyce Theater to watch the New York debut of Dimensions Dance Theatre. While waiting for the curtain to rise, a friend and I were chatting about the fact that I used to know dozens of dancers across nearly every American ballet company. The rosters of companies looked more like a personal year book with a collections of friends from summer intensives, year-round finishing programs, and companies. Today, most of those peers are in the age range of 30-38 years old. In pondering this part of my history, I noted how much things had changed in a short period of time. Nearly everyone who is still dancing are now Soloists and Principals in their respective companies or have left bigger company jobs to dance with smaller ones similar to Dimensions Dance Theatre. One of the most widely known facts is that dancers have relatively short careers. The top inquiry I field regularly in conversation questions the exact age dancers take their final bows. I’ve put a lot of thought into this over the years. So, why not share this retirement chart that I’ve developed and offer some insight to those of you with this common question.

Let me preface this chart with a few things. One of the best pieces of advice that I overheard after a colleague became injured was that there is no timeline to a dance career. I agree with this statement strongly. This is simply my generalized assessment of career duration based off of my own experience and direct research.

The Whole Pool of Dancers (any child that has ever taken class): A great majority of the American female population takes recreational dance classes by the age of 8. Out of this massive pool of dancers very few continue beyond their elementary school years. My assumption is that this is due to lack of interest, curiosity about other activities, financial circumstances of families, and more. I do not believe that many of those who stop dancing do so due to injury.

Middle School Age Dancers: A great deal changes during the middle school years. Aside from the obvious body changes that take place, dancers tend to grow greater interest in social activities with their peers. The next large majority of dancers leave dance during these years. I believe this is due to curiosity about other activities outside of dance (especially if friends are involved), revelations that their changing bodies do not fit certain dance aesthetics, and increased interest in social events. It is also around this age when dancers interested in a performance career will require a greater commitment to classes. Instead of a once or twice a week after school activity, dancers with career hopes will need to be in class 4-6 days/week and commit to longer hours in the studio.

High School Age Dancers: There are many changes for dancers during their high school years. The early years often mimic the end of middle school with some dancers still growing into their bodies and stress over focusing wholly on dance vs. exploring other interests. By the time a dancer is 16-17 years old, they must strongly consider whether they will fully commit to an attempt at “making it,” go to college before pursuing a performance career, or quit and focus on their academic studies. A very small group will choose to continue forward to a finishing school to complete their training with hopes of gaining professional employment. A majority of the rest in the ballet world will end their dance training here. In other genres of dance (modern/musical theatre/commercial styles), it is more common for dancers to attend college before considering professional employment.

Finishing School: Only about 25-50% of dancers who attend finishing school are likely to achieve a professional career. During these final years of training, dancers are pushed to their limit with a multitude of classes, school rehearsals, and (sometimes) company rehearsals. Most dancers need to move away from home as teens to attend. So, they must begin managing how to live, eat, and socialize on their own. Items that can pull this final stretch of training off track include injury (often chronic), disordered eating, lack of balance between work and social life, disappointment (class placement, casting, audition rejections), realization of potential, and more. This and the first two years of a performance career are probably the most difficult periods when it comes to sustaining a dance career.

First Few Years as a Professional: At least 25% of dancers who make it into companies will retire within the first few years of their professional career. Many arrive in a company and think that the success they had throughout their training will automatically roll over to their new positions. But the first few years in a company are a tricky minefield. Most who obtain a career enjoyed dancing leading roles in school performances. When these dancers arrive in a company and are relegated to the back of the studio as an understudy, perform mostly walk on roles in full length ballets, or only receive opportunities to perform dancing roles in the 2nd or 3rd cast of ballets, it isn’t uncommon for dancers to lose interest. Additionally, many dancers sacrifice their social lives during the final few years of their training, only to realize that they have been missing out. Sometimes, dancers will attempt to rectify this imbalance. This can result in loss of interest in dance, loss of focus on work, or too much partying. Also, the mental stress of being responsible for one’s own product and the physical stress of an entire work day dancing can often lead to burn out and injury. For this reason, there is a rather large number of dancers who only get to enjoy 1-3 years of their professional career before retiring and moving into a different field.

Mid 20’s: I’ve noticed that the next cohort of dancers usually retire around the age of 24-27. If a dancer is able to adapt to company life, they usually have a good 5-6 years before they suffer their first major injury. We all have minor injuries on a regular basis, from muscle strains to tweaked ankles, sore backs, and more. But the first major injury dancers have often requires more than a month of recovery or surgery. When this happens, dancers return without the knowledge and maturity to build back into their dancing. Many dancers, fearful that they may lose their jobs, get back to work too quickly and end up re-injuring themselves. Often this second injury causes directors to question a dancer’s ability to perform their job duties (leading to non-reengagement of contracts) or a dancer becomes frustrated and chooses to move on from their performance career.

Early 30’s: A majority of the dancers who retire at this age are long-time corps de ballet dancers who were able to sustain their career, but never had the privilege of promotion into higher ranks of companies. Dancing in the corps de ballets puts the greatest amount of stress on a dancer’s body, especially dancers who also get to perform soloist and leading roles. The body can only take so much. So, it makes sense that a corps dancer’s body is likely to give out before a Soloist or Principal (who may dance more demanding roles, but is usually given more time to recuperate). Additional factors that contribute to this group retiring also include frustration with lack of advancement, directors needing to free up funds for less experienced/less expensive dancers, aging out of roles like peasants, and more.

Mid 30’s: The next cohort of dancers who retire tend to be Soloists. These dancers don’t have the demands of dancing corps roles, so their bodies last longer. Many dancers really begin to complain about recurring injuries and constant aches during their mid-30’s. This age group also seems to feel very fulfilled with the amount of time that they have been dancing professionally. Most soloists appear to hang up their slippers before their bodies completely falls apart.

Principal Dancers: Based purely on my own experience, Principal dancers tend to dance until their body can no longer continue to dance at the high level their rank requires. It is very rare for a director to force a leading dancer to retire. So, it is usually up to the Principal to create a valid timeline as their body and technique begin to falter. Men tend to retire in their late 30’s because their backs can’t handle the load of partnering much further beyond this age. For women, especially those with natural physical facility, it isn’t uncommon to dance into their early 40’s.

Modern Dancers: It seems that the only dancers who completely defy the stressors of an aging body are those who perform works in the genre of modern dance. I have seen professional modern dancers working from the age of 15 to 74 years old. Modern dance has a more realistic progression of roles for dancers of all ages, so it isn’t wildly uncommon to see mature dancers continuing to find artistic fulfillment well into middle age and beyond.

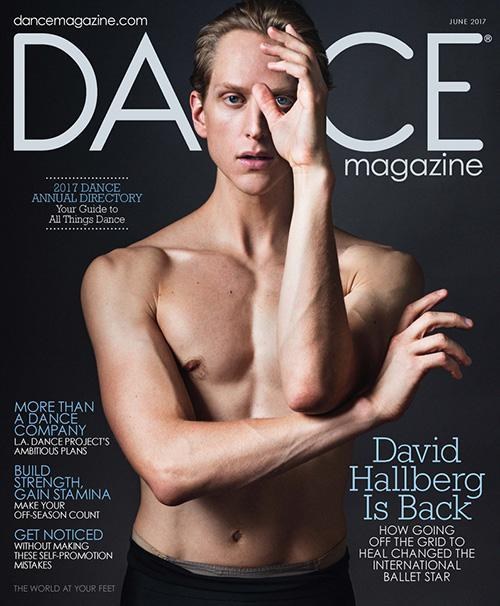

The first day that I worked with American Ballet Theatre was filled with an enormous sense of accomplishment and a great deal of anxiety. It was during my final year of training at the School of American Ballet when I was one of 4 boys offered a trial contract with the company to go on tour to the Kennedy Center as a member of the corps de ballet in MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet (before ABT’s JKO school existed). I was David Hallberg’s 2nd cast when he would step out of the corps as the 2nd cast for Benvolio and I was tasked with learning intricate fencing and intertwining corps sequences from the moment I walked into the studio. My excitement of dancing with my dream company was equally balanced by my stress level, as I had never been shown so much choreographic material at once or been expected to retain it with such immediacy. This style of learning was a grand departure from what I was used to in school when it came to learning new material and preparing to perform it. Now that I have moved forward into the realm of choreography and coaching for a range of student and professional dancers, I use experiences I’ve had as a tool to help prepare dancers in the most appropriate, economical fashion possible.

The first day that I worked with American Ballet Theatre was filled with an enormous sense of accomplishment and a great deal of anxiety. It was during my final year of training at the School of American Ballet when I was one of 4 boys offered a trial contract with the company to go on tour to the Kennedy Center as a member of the corps de ballet in MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet (before ABT’s JKO school existed). I was David Hallberg’s 2nd cast when he would step out of the corps as the 2nd cast for Benvolio and I was tasked with learning intricate fencing and intertwining corps sequences from the moment I walked into the studio. My excitement of dancing with my dream company was equally balanced by my stress level, as I had never been shown so much choreographic material at once or been expected to retain it with such immediacy. This style of learning was a grand departure from what I was used to in school when it came to learning new material and preparing to perform it. Now that I have moved forward into the realm of choreography and coaching for a range of student and professional dancers, I use experiences I’ve had as a tool to help prepare dancers in the most appropriate, economical fashion possible.

There are a couple of ways in which students are treated differently when it comes to preparing for performances. Those moving in the direction of a professional career will often learn choreographic content that is progressively closer to what professionals perform. When I learned my first classical pas de deux at the age of 15, I learned it off a VHS tape (yep, throwing it back) of fully realized dancers in performance. While we were young and had not completely developed as artists, we put in our best effort and performed the pas de deux as we saw it on the video. While a teacher or coach can offer a simplified version of choreography, student dancers will (for the most part) perform the same steps as professionals. The only difference here is that technical tricks like pirouettes may not be performed with as many rotations or certain sequences may be simplified for safety until enough strength and coordination is gained.

One of the main differences when it comes to coaching a student is the amount of time allotted to learn the work, clarify material, and build stamina. When I performed the Don Quixote pas de deux for my graduation performance at the Kirov Academy of Ballet (you can see footage here), we began rehearsing for our May show at the beginning of February. With 2-4 hours of rehearsal each week on the pas de deux alone plus additional time for rehearsal of the variations, we had many hours of practice to ensure that we knew the steps, understood the characters, and had the physical prowess to get through this challenging, pyrotechnic 8 minute piece. Students are often given a greater cushion of time to allow them to safely find their way through the material of a professional while still working as a student.

The final aspect of coaching kids that differs from working with pros comes in the form of how the coach approaches corrections. For me, I find that there is a huge emotional aspect when it comes to giving feedback, as it involves giving that feedback and seeing how the student responds both physically and psychologically. I have been coaching students to compete at the Youth America Grand Prix (YAGP) international ballet competition for nearly 4 years. My approach has changed over this period as I have gathered more experience working with different kids from a range of schools. When I first started working with new students, I would coach them in the same way that I was throughout my final years of training and as a professional. I gave direct feedback that got straight to the point without any coddling or wasted time. What I found was that some students felt demoralized by certain corrections, as they weren’t used to this style of coaching, weren’t taught how to receive corrections in that way, or didn’t understand that a correction wasn’t an attack on them as a person. Dance can be confusing in that way because while we are correcting the body’s form and the way one portrays a character with their face, it doesn’t mean that there is something wrong with a dancer as person. It is just our pathway to express our art form and necessary to convey characters through dance. Now, when coaching my students, I make sure that we take time throughout lessons to discuss corrections, why I am giving them, and how they should be addressed.

This past week, 4 students I worked with competed in the final round at YAGP. One 13 year old in particular that I worked very closely with this season has made great progress throughout our rehearsal process. When we began, I offered a warmer approach to guiding her through corrections. As she developed during our time together, I began to alter my approach to working with her and started to give more direct feedback. By the end of the final round of the competition while discussing how she felt about her performances, it became clear that she had matured to a point where she understood critical feedback and had began self-critiquing her performances. In that moment, I recognized that she was ready to begin working in a more professional format. I sat her down and explained that my approach with her in class and rehearsals will be changing. I noted that I will greatly increase my expectations of her in class and rehearsals and that she should be prepared for a much tougher approach from me. I am a big advocate of teaching emotional well-being to my students and I feel it is important to carefully guide kids and teens into a state of understanding when it comes to extremely critical feedback. With this student in particular, she is there.

I tend to go back and forth between periods of working with students and professionals as a coach. Generally, when I work as a coach with professionals, it often comes in the form of me choreographing on them and then providing feedback to ensure that they perform my work at the highest caliber. After reading the above information, you can probably see where I am going when it comes to explaining the coaching process with pros versus students. Coaching professionals is much different than working with kids. There isn’t as much emotional coddling in a professional work environment. With less time available in most professional rehearsal processes, corrections are given in a matter-of-fact way and it is expected that they will immediately address issues. We also expect dancers to be critiquing themselves and working to fix issues before we have to call them out.

Beyond all of this, most rehearsal periods are much shorter for the pros. As I was discussing at the beginning of this post, going from learning choreography as a student to rehearsing with American Ballet Theatre, I experienced a major learning curve. There wasn’t really a progressive period from student to professional where I was shown how to learn choreography at the speedier rate in a company. This tends to be a sink-or-swim period for new dancers coming into their own. I was one of the lucky ones that figured out how to learn material at a much faster pace. Without much guidance, many talented dancers fall behind their peers with this new expectation. To help a bit with the learning curve, many apprentices and young corps dancers spend multiple hours of their rehearsal days standing in the back of the room understudying roles. They are essentially being taught how to retain material faster. For this reason, it is so important that professional division students in schools and early career dancers that are asked to understudy take this role very seriously.

There is no guidebook when it comes to coaching dancers to perform at their best. But it is important that those of us who are coaching students don’t blindly walk into a studio and treat dancers exactly as we were taught. It is important to look at the individual dancer and assess what their needs are. Sometimes, this comes in the form of finding appropriate material for the physical form of a students. While at other times, it includes determining how to build a dancer’s emotional stamina. If this process is appropriately followed for the individual, we will create professional dancers who can function properly in the challenging work environment that often accompanies company work. And in the end, students who become company dancers will have all of the tools they need to become efficient at their jobs and help their organizations turn out the best product possible.