Teaching “One-Off” Classes

An Informational Blog about the Post-Performance Careers of Professional Dancers

One of my goals in creating this blog is not only to share my own stories and experiences as I navigate my post-performance career, but to also offer a platform for my peers to discuss what life is like after they have stepped off the stage. My first guest blogger for Dancing Offstage is Michael Patterson, Artistic Director of Patterson School of Ballet. I met Michael while he was teaching in the Philadelphia area and have followed him as he moved to Erie, PA, eventually opening his own school. Read on to hear his story and the challenges he has faced as he traverses his second career in dance. Enjoy!

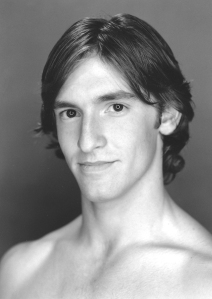

There are many roads to opening and operating a pre-professional ballet school. This is my story. Every story starts somewhere and mine began in Titusville, PA on my family’s dairy farm.

Titusville’s claim to fame is Edwin L. Drake who is credited with the start of the oil industry and football’s John Heisman. Had it not been for PBS, I never would have known that ballet even existed; there were no dance studios in Titusville. No one that I knew had ever seen a ballet before. But at the age of 6, my sister and I were watching our local PBS station and The Nutcracker came on starring Gelsey Kirkland and Mikhail Baryshnikov. I remember being totally mesmerized by their grace and strength and we were glued to the television throughout the duration of the program. I told my mom shortly thereafter that I wanted to take ballet. Her response was, “if that’s what you want to do,” and she went back to work.

At the age of 11, after losing interest in other activities (including baseball, soccer, and piano lessons), I approached my mom and again asked if I could take ballet. This time she signed me up for classes with my sister at Cathy Turner’s Dance Studio in nearby Franklin, PA. It wasn’t until I was 12, at the recommendation of my teacher, that I began studying classical ballet under the direction of Sharon Filone in Erie, PA. Later, I studied at the Central Pennsylvania Youth Ballet under the direction of Marcia Dale Weary and then joined Pennsylvania Ballet in 2002.

While dancing with this company, I was given many opportunities to perform lead roles and toured internationally (with Edinburgh International Arts Festival in Scotland being a highlight). Though I was progressing within the company, I was battling an injury that wouldn’t heal, even with time off. It was at this point that I left Pennsylvania Ballet and began teaching for the legendary American ballerina, Barbara Sandonato, whose daughter I had danced with in the company.

Though I had taught at summer programs on lay-offs, this was my first experience teaching in a school where I was responsible for the long-term training of students. It was also here where I got a crash course in dealing with parents, staging choreography, and setting schedules. With Ms. Sandonato’s guidance, I was able to feel more comfortable in a classroom setting, as well as honing my abilities to produce results and mentor aspiring students. In 2013, I was approached by a local university back in Erie, PA to head their children’s dance program. This new proposition would also serve as an opportunity for me to resume my college education.

When I arrived in Erie, there were only three students enrolled in the program I was to head. In order to promote the school, I dropped off flyers at many of the local businesses and by mid-year had 12 students in my classes. The program was nearly self-sustaining when it was cut only nine months later due to an unforeseen financial situation at the university. I had already planned a summer intensive that had enrolled 20 students, and I was crushed. It was at this time that a family whose daughter was returning to the area (after many injuries at another school) asked if I was interested in starting a school. At the conclusion of my intensive, I decided to meet with a lawyer who helped me incorporate my own school. The Patterson School of Ballet was born on August 18, 2014.

In seeking a home for my school, I looked at many places. But due to financial constraints, I couldn’t afford to renovate a brand new space. As luck would have it, and with some persistence, I found a former yoga studio that was already equipped with a cushioned floor, mirrors, and had been modeled in a way that befit a dance school. The interior was a warm inviting atmosphere, reminiscent of a lodge, and didn’t have the clinical feel that most studios have. I wanted a studio where moms and dads would feel comfortable and guest teachers would feel welcomed. Also adding to the warmth of the studio was a gas fireplace, which is great for Erie winters, and double doors that can open during the summers to allow the warm lake breeze to pass through the studio.

There are many challenges in having a small business, especially a ballet school in Erie. First, the community is inundated with dance schools. I set out to make something different in our community using lessons instilled in me as a child . . . “jack of all trades, master of nothing.” Our students learn how to master classical ballet technique, which gives them the ability to evaluate other dance forms and learn them much more quickly. While they continue to make strides in their classical education, many of the students attend high schools in the area that offer other forms of dance as an alternative to their physical education requirements. So, our students still have the benefit of being exposed to other dance forms. As I mentioned previously, affordability prevented me from building the ideal studio I dreamt of right away. As the Patterson School of Ballet has grown, we recently held a successful fundraiser to raise enough money to build sprung floors in our studio, which will be much better for the long-term health of my students.

When it came to scheduling our Fall classes for the first time, there were many factors that were also challenging. Our greatest challenge was the limitation on evening class times for students. It was difficult to keep up with the numerous school districts, as well as private schools, so I spoke with many parents about class times that would be convenient for them. It was important for me to have my students take the necessary number of ballet classes that a serious program requires. Another aspect that was crucial to the success of the program was finding a pricing scale that was competitive with surrounding studios. Most studios in our area charge very little for classes, with most charging as little as $10/hour. The Patterson School of Ballet’s tuition begins at $10/hour, but as students take more classes the price drops so students that are taking 14 hours of class have an hourly rate that’s under $6/hour. Unlike other studios in our area, our program is all-inclusive, meaning that students have regular guest/master teachers at no additional cost and there are no costume, rehearsal, or performance fees associated with our program. Any rehearsals are in addition to class time, so as to not take away from the purpose of our pre-professional training curriculum. As they say, you get what you pay for. At Patterson School of Ballet, parents make an investment in their training, without ending up with a closet full of costumes.

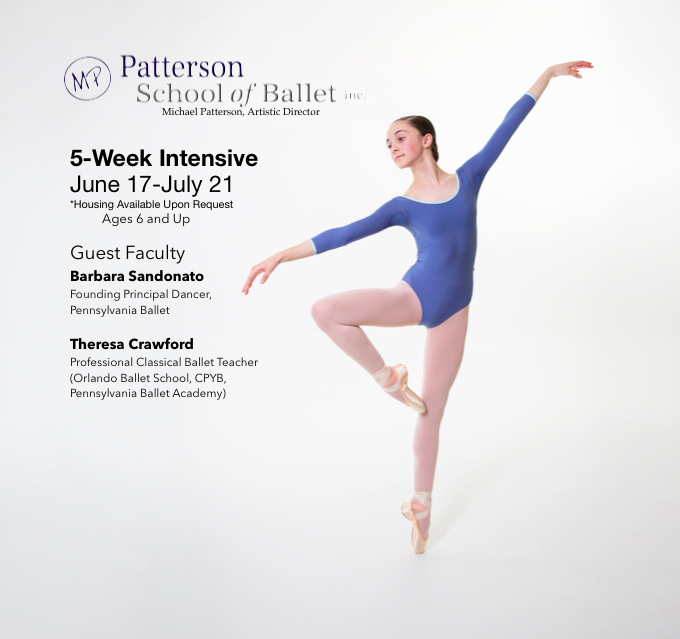

The Patterson School of Ballet’s curriculum is unique to the area, as we keep small class sizes and a proven graded-level ballet syllabus. Our program offers superior training, but also provides many performance opportunities. Since our first summer program, Patterson School of Ballet has established a 5-week intensive, a super hero half-day camp, and an August intensive. We have had guest faculty and master teachers Theresa Crawford, Matthew Carter, Abigail Mentzer, Melissa Gelfin, Danae Patterson, Frank Galvez, Catherine Gurr, Halle Sherman, Bob Vicary, Elysa Hotchkiss Walls, and Barbara Sandonato (who serves as Artistic Advisor to our school). Our students have had the opportunity to watch company class with Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre, Pennsylvania Ballet, and the Joffrey Ballet, and have seen performances by them on numerous occasions. Our students also regularly participate in enrichment programs provided by Ballet In The City, where they’ve had the opportunity to work with Sonia Rodriguez, Francis Veyette, Lauren Fadeley Veyette, and other fabulous teachers. Performances include outreach with local non-profits in our area, in addition to our year end June Show. This year’s showcase will include Act II of Swan Lake with guest artists Catherine Gurr and Logan Martin.

It can be hard to deal with the competitive nature of having a business in the local dance community. But at the end of the day, I wouldn’t give up my school. While there are many in our community who are incredibly supportive, unfortunately, there are always those from other local organizations that will do or say anything to discredit you personally and professionally. However, it is very important for me to not let that enter in through the doors of my studio. Although the students are not my children, I do have a responsibility to mentor them and help them become the best version of themselves, both inside and outside the studio. My mission is to enrich children’s lives and provide opportunities for personal growth and achievement by utilizing the skills developed in the studio. Any program should be an investment in a child’s future. It is not only our goal to train professional dancers, but to also give students a clear understanding of what it takes to be good at something, to take pride in knowing that you do it well, and to aspire to be more.

Check out more about Patterson School of Ballet at www.pattersonschoolofballet.com

The first day that I worked with American Ballet Theatre was filled with an enormous sense of accomplishment and a great deal of anxiety. It was during my final year of training at the School of American Ballet when I was one of 4 boys offered a trial contract with the company to go on tour to the Kennedy Center as a member of the corps de ballet in MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet (before ABT’s JKO school existed). I was David Hallberg’s 2nd cast when he would step out of the corps as the 2nd cast for Benvolio and I was tasked with learning intricate fencing and intertwining corps sequences from the moment I walked into the studio. My excitement of dancing with my dream company was equally balanced by my stress level, as I had never been shown so much choreographic material at once or been expected to retain it with such immediacy. This style of learning was a grand departure from what I was used to in school when it came to learning new material and preparing to perform it. Now that I have moved forward into the realm of choreography and coaching for a range of student and professional dancers, I use experiences I’ve had as a tool to help prepare dancers in the most appropriate, economical fashion possible.

The first day that I worked with American Ballet Theatre was filled with an enormous sense of accomplishment and a great deal of anxiety. It was during my final year of training at the School of American Ballet when I was one of 4 boys offered a trial contract with the company to go on tour to the Kennedy Center as a member of the corps de ballet in MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet (before ABT’s JKO school existed). I was David Hallberg’s 2nd cast when he would step out of the corps as the 2nd cast for Benvolio and I was tasked with learning intricate fencing and intertwining corps sequences from the moment I walked into the studio. My excitement of dancing with my dream company was equally balanced by my stress level, as I had never been shown so much choreographic material at once or been expected to retain it with such immediacy. This style of learning was a grand departure from what I was used to in school when it came to learning new material and preparing to perform it. Now that I have moved forward into the realm of choreography and coaching for a range of student and professional dancers, I use experiences I’ve had as a tool to help prepare dancers in the most appropriate, economical fashion possible.

There are a couple of ways in which students are treated differently when it comes to preparing for performances. Those moving in the direction of a professional career will often learn choreographic content that is progressively closer to what professionals perform. When I learned my first classical pas de deux at the age of 15, I learned it off a VHS tape (yep, throwing it back) of fully realized dancers in performance. While we were young and had not completely developed as artists, we put in our best effort and performed the pas de deux as we saw it on the video. While a teacher or coach can offer a simplified version of choreography, student dancers will (for the most part) perform the same steps as professionals. The only difference here is that technical tricks like pirouettes may not be performed with as many rotations or certain sequences may be simplified for safety until enough strength and coordination is gained.

One of the main differences when it comes to coaching a student is the amount of time allotted to learn the work, clarify material, and build stamina. When I performed the Don Quixote pas de deux for my graduation performance at the Kirov Academy of Ballet (you can see footage here), we began rehearsing for our May show at the beginning of February. With 2-4 hours of rehearsal each week on the pas de deux alone plus additional time for rehearsal of the variations, we had many hours of practice to ensure that we knew the steps, understood the characters, and had the physical prowess to get through this challenging, pyrotechnic 8 minute piece. Students are often given a greater cushion of time to allow them to safely find their way through the material of a professional while still working as a student.

The final aspect of coaching kids that differs from working with pros comes in the form of how the coach approaches corrections. For me, I find that there is a huge emotional aspect when it comes to giving feedback, as it involves giving that feedback and seeing how the student responds both physically and psychologically. I have been coaching students to compete at the Youth America Grand Prix (YAGP) international ballet competition for nearly 4 years. My approach has changed over this period as I have gathered more experience working with different kids from a range of schools. When I first started working with new students, I would coach them in the same way that I was throughout my final years of training and as a professional. I gave direct feedback that got straight to the point without any coddling or wasted time. What I found was that some students felt demoralized by certain corrections, as they weren’t used to this style of coaching, weren’t taught how to receive corrections in that way, or didn’t understand that a correction wasn’t an attack on them as a person. Dance can be confusing in that way because while we are correcting the body’s form and the way one portrays a character with their face, it doesn’t mean that there is something wrong with a dancer as person. It is just our pathway to express our art form and necessary to convey characters through dance. Now, when coaching my students, I make sure that we take time throughout lessons to discuss corrections, why I am giving them, and how they should be addressed.

This past week, 4 students I worked with competed in the final round at YAGP. One 13 year old in particular that I worked very closely with this season has made great progress throughout our rehearsal process. When we began, I offered a warmer approach to guiding her through corrections. As she developed during our time together, I began to alter my approach to working with her and started to give more direct feedback. By the end of the final round of the competition while discussing how she felt about her performances, it became clear that she had matured to a point where she understood critical feedback and had began self-critiquing her performances. In that moment, I recognized that she was ready to begin working in a more professional format. I sat her down and explained that my approach with her in class and rehearsals will be changing. I noted that I will greatly increase my expectations of her in class and rehearsals and that she should be prepared for a much tougher approach from me. I am a big advocate of teaching emotional well-being to my students and I feel it is important to carefully guide kids and teens into a state of understanding when it comes to extremely critical feedback. With this student in particular, she is there.

I tend to go back and forth between periods of working with students and professionals as a coach. Generally, when I work as a coach with professionals, it often comes in the form of me choreographing on them and then providing feedback to ensure that they perform my work at the highest caliber. After reading the above information, you can probably see where I am going when it comes to explaining the coaching process with pros versus students. Coaching professionals is much different than working with kids. There isn’t as much emotional coddling in a professional work environment. With less time available in most professional rehearsal processes, corrections are given in a matter-of-fact way and it is expected that they will immediately address issues. We also expect dancers to be critiquing themselves and working to fix issues before we have to call them out.

Beyond all of this, most rehearsal periods are much shorter for the pros. As I was discussing at the beginning of this post, going from learning choreography as a student to rehearsing with American Ballet Theatre, I experienced a major learning curve. There wasn’t really a progressive period from student to professional where I was shown how to learn choreography at the speedier rate in a company. This tends to be a sink-or-swim period for new dancers coming into their own. I was one of the lucky ones that figured out how to learn material at a much faster pace. Without much guidance, many talented dancers fall behind their peers with this new expectation. To help a bit with the learning curve, many apprentices and young corps dancers spend multiple hours of their rehearsal days standing in the back of the room understudying roles. They are essentially being taught how to retain material faster. For this reason, it is so important that professional division students in schools and early career dancers that are asked to understudy take this role very seriously.

There is no guidebook when it comes to coaching dancers to perform at their best. But it is important that those of us who are coaching students don’t blindly walk into a studio and treat dancers exactly as we were taught. It is important to look at the individual dancer and assess what their needs are. Sometimes, this comes in the form of finding appropriate material for the physical form of a students. While at other times, it includes determining how to build a dancer’s emotional stamina. If this process is appropriately followed for the individual, we will create professional dancers who can function properly in the challenging work environment that often accompanies company work. And in the end, students who become company dancers will have all of the tools they need to become efficient at their jobs and help their organizations turn out the best product possible.

The first time I heard anything relating to social media was during my time living in the dormitory at the School of American Ballet. There was a young student, who at 16 years old was using the Myspace network as a sort of coming of age and coming out. Essentially, while I didn’t come to know the term social media for years, my first impression of MySpace was that it was a site used for the sexually promiscuous and for those willing to risk their lives in the process of making bad decisions. It probably makes sense why it took another 2 years and the influence of my first love to get me to join a world that would eventually become an integral part of my (and many others) life.

I reluctantly joined MySpace back in 2003 and, like most any Xennial, quickly adjusted to a life where we shared the thoughts inside our heads with anybody who dares to cross our profiles. It only took me a few weeks to go from lurking to writing short blog posts for my friends and colleagues (at the time, I wouldn’t dare let my family see my profile). As I learned that MySpace wasn’t what would eventually become Tinder or Grindr, I began sharing more and more of my daily experiences and personal thoughts. Just like the judgment of my peer at the School of American Ballet, my colleagues at Pacific Northwest Ballet began to judge my decision to share more of my life publicly, both behind my back and to my face. I remember a moment when a Principal dancer who was most rarely kind or friendly towards me pulled me aside and demanded, point blank, that I needed to stop blogging on my MySpace page. I remember the conversation that followed with my (now) husband, where I told him I felt that it was important that I share my life publicly because it was an expression of myself as an artist and human. In 100 years, they may say I was one of the pioneers of social media. My husband’s response (who is Gen X) was supportive, but also stated the fact that he also would never share his personal life in the same way. We spoke at length that night as I evaluated whether I was going to continue down this path of being as publicly honest and straightforward as I could or whether I was going to carefully guard my life experiences to avoid anybody vengeful using my public sharing against me either professionally or personally.

If you are reading this blog, it is quite clear which decision I made. After some time and over 400 blog posts on MySpace, I transitioned my full energy to Facebook. It took me a few years to start writing in any type of blog format again, but it eventually happened. If you don’t know my story, I’ll share it in brief here. But you should really browse my first blog, Life of a Freelance Dancer, if you want the whole story. While I had become adept at using Facebook, my social media expertise didn’t really become apparent until I began blogging again. I didn’t start up my second blog out of boredom, expression, or curiosity of the reactions of others. Instead, I did it out of fear and necessity. After transitioning away from dancing with a major ballet company to stretch myself as an artist with a small, grassroots contemporary ballet company, I became injured and was eventually fired because of this injury. It was too late for me to get healthy enough to participate in audition season and I couldn’t imagine moving again so soon after relocating my home and family 3,000 miles for the job with this company. I knew I could write, but I didn’t know if people would read anything outside of random musings and thoughts from my days. But I pushed forth and began sharing my experiences and thoughts on Life of a Freelance Dancer as I attempted to salvage a failed attempt to try something new with my career. The first handful of posts, I remember friends reaching out and asking for me to stop sharing my blog on Facebook or they would unfriend me. They felt like I was marketing on a personal platform, kind of in the same vain as a pyramid scheme. I pressed forth anyway, and eventually my blog became so popular that I didn’t have to audition for work, I spent nearly 35-40 week’s on the road dancing yearly, hundreds of people were reading my blog daily in over 120 countries around the world, and I was included on a list of 49 Creative Geniuses Who Use Blogging to Promote Their Art. I didn’t quite realize it was happening because I was living it, but my social media star had risen. I had become a role model for many hopeful freelancers, working professionals, and people looking for inspiration in general. It was nice that I didn’t have to worry too much about what I posted because my audience mostly consisted of adults and students in their late teens who were prepping for a career.

It was thanks to my willingness to offer the most candid presentation of my life and my life’s work that I had achieved all that I had in a short 4 years. After I was featured alongside New York City Ballet Principal Megan Fairchild in the January 2016 issue of Dance Magazine for being an innovator in social media, I was approached by Kimberly Falker of the Premier Dance Network to host my own podcast show on her network and iTunes. Suddenly, I had a massive platform to continue doing something that dancers were never really known for, sharing my voice as a part of my art. My brand is candor and it is daring due to the fact that the dance world doesn’t necessarily function on fact. It can be dangerous to be vocal about the less ideal parts of our art form, like sexual harassment, injury, burn out, anxiety, or emotional training. But my willingness to share my experiences and stories with the dance world and beyond has really pushed me into the spotlight more than I ever was while putting all of my sweat and tears into my performance career.

Now, the point of me sharing all of this information isn’t to create a documented timeline of my social media experience or gloat about my successes that have arisen from being an over-sharer. Instead, I am writing to discuss a challenging topic that I have recently been facing within my personal social media. As my interest in Facebook has steadily declined (mostly due to algorithms, the political mess of 2016, and too much noise instead of personal connection), I have turned more and more of my attention and effort to Instagram. I was quite resistant to join this photo/video sharing network mostly out of fear that it would take up more of my non-existent time. Although I delayed, I knew it was inevitable that I would eventually join this platform and immediately fall in love with this visual app. I’ve always had a knack for taking photos and I love the idea that Instagram offers me the opportunity to show my followers what it looks like to see the world through my eyes. I already had a good following on Facebook and on my Life of a Freelance Dancer blog when I joined. So, I never really felt the need to build an audience of followers beyond my family, friends, colleagues, and peers. That was until my recent falling out of love with Facebook.

As I have transitioned more of my attention to my Instagram (https://www.instagram.com/bkerollis/), I have been slowly gathering followers who enjoy my content and want to follow my career and lifestyle. I feel that I’ve gotten particularly good at cultivating a following within my network just by posting the things that I enjoy and the work that I am doing. These items include dance, city life, skyscrapers, and imagery of my travels. But my wishes to grow a vast audience, brand, and network beyond my daily reach of people I personally interact with has become a challenging conversation that involves who my audience is, what communities I belong to, and my own personal integrity.

For me and my regular brand of candor, I want to post whatever images and content I want to at that moment. But things have changed a lot for me over the past few years. I am no longer backstage dozens upon dozens of time during the year and promoting myself solely as a performing artist. My audience has widened in many ways. I work with students ranging from young hopeful 10 year olds up to recreational 80 year old adults. My audience consists of everybody from small kids to gay men to Broadway dancers, ballet dancers, podcast listeners, blog readers, fans of my photography, parents of my students, and more. As I said earlier, I have been slowly building my Instagram audience. But I now feel ready to go all in to promote my choreography, teaching, and media work to a much larger audience on an international scale. The main challenge here is how does one build an audience with integrity while catering to a range of communities as diverse as my own. I have really struggled with this idea lately and, perhaps, this is the reason that I am ruminating over this publicly. I don’t want to post videos of myself dancing, as I would rather spend my time focusing on making my students into amazing dancers. I already had my performance career. Sometimes, I find it tempting to post practically nude photos of myself to cater to the gay community and gather easy follows. Sex sells and I still have my dancer body, so it could be a cheap sell. But I have children looking at my account, parents monitoring my activities, and being a married man I don’t need to market myself in that way (though I will post the occasional artistic nude-ish photo). I also don’t like to build an audience using hashtags like #followforfollow, as I feel that there is no investment from those followers beyond patting them on the back. I want people who see my content to be invested in what I am doing, sharing, and promoting.

So, at the moment, I am finding myself caught in a social media pickle. How does somebody like me market to a vast audience with differing tastes, receive brand sponsorships, gain opportunities in and out of my field, and add followers who are invested in the work that I am doing? I’m not sure that I really know at the moment. But for anybody else who has found themselves in a similar situation, I can tell you that it is important to set standards for yourself and move forward with integrity. If you have integrity, no matter the outcome, you will always look back and be proud that you didn’t sell out to get ahead. I have chosen to move forward with integrity and am trying to set certain standards in my social media practices. Photographs that include nudity will only be shared if they are artistic and tasteful. Footage of myself dancing my own choreography in a class will only take place if I am regularly posting footage of my actual students dancing it with me, my attention is focused on them for the entirety of the class, and filming doesn’t take place more than once or twice a month. And, lastly, I will build an audience based purely off of people who want to follow me, and not off of some idea of reciprocity where somebody disinterested in my content will follow me only because I have followed them.

With all of this said, I am curious if you have found yourself in this same type of situation. Do you have a wide range of audience members and have trouble making sure that your content is completely appropriate for all of your viewers? What do you think of posts where the teacher is dancing front and center in a class they are supposed to be teaching? Do you believe that you should build your audience and then cultivate content to keep them interested or that you should only seek out followers who found you because they initially liked your content? Feel free to leave a comment here or to reach out to me on Instagram to let me know your thoughts!

There are so many lessons to be learned in this life. In the past few weeks, I spent some time with a handful of my students coaching them while at the Youth America Grand Prix competition. I was so impressed to see how they held their own under the pressures of competition, and a handful of them even placed (one of them won the Grand Prix, two won 2nd & 3rd place in their categories, and a handful placed in the Top 12). While my job was to warm my kids up, hone in their focus, and provide support no matter the outcome of what happened onstage, I learned a very important lesson. Read on to see what that lesson was along with a handful of others I’ve learned since retiring from the stage.

1. One of the most surprising lessons I’ve learned since retiring has been that I don’t have to take class every day to maintain my technique. As my schedule has become overwhelmingly booked with teaching, coaching, choreographing, podcasting, and blogging, I have had difficulty making it to class as often as I would like. But taking class 2-4 times each week (as opposed to 5-6 times) actually allows my body to recover and feel better from day to day. While there are a few areas I feel that I’ve lost ground in (adagio and extended stamina), I can still perform a majority of the feats I executed daily during my stage career. And if something isn’t working one day and it stresses me out in the moment, I just remind myself that I’m retired from the stage and class is now wholly for me again.

2. With no intention for any negative connotation, a performance career is very selfish. In order to perfect one’s art, we must spend countless hours working on ourselves and focusing great attention to personal detail. Beyond this, due to the brevity of our careers, we tend to feel that we need to achieve every goal we set, gain every opportunity available, get cast in every role we dream of, and climb up the promotion ladder as fast as possible. It has been liberating to step outside the selfishness of my own performance career and to allow my focus to include others. In the past few weeks while coaching a handful of students to compete at Youth America Grand Prix , I suddenly became very aware of how invested I was in the success of my students. I was so extremely hopeful for them to perform well because their success and happiness was also mine. This post-career life has taught me that the success of many is greater than the success of one.

3. This may sound odd since my attention has shifted from fully focusing on my own instrument. But my technique has improved greatly since I began teaching and coaching dancers. While teaching my students, I often have to find unique ways to express muscle engagement, joint movement, placement, balance, coordination, and more. I find myself evaluating my own work in class much more meticulously as I explore the best way to convey information to students while teaching. This has netted an overall positive in my own dancing, as I have a greater understanding of many things that I hadn’t grasped during my performance career.

4. I didn’t always notice this, but there were many times that I wish I had a certain type of support, guidance, or mentorship during my career. I left home at the age of 17 to train and I moved across the country into my own apartment at the age of 19 to start my career with Houston Ballet. As I transitioned to Pacific Northwest Ballet, became an adult, and eventually navigated my way through a national career as a traveling freelancer, I often wished that I had more support in many ways. Now that I have stepped into a more educational leadership role, I have been baffled by the number of dancers who have reached out to me in need of physical, emotional, and financial support. If these are the dancers that are asking for help, I can’t imagine the number of dancers who don’t ask. One thing that has become abundantly clear to me is the need for support in our community and the lack of resources, access, and assistance available to help our the real-life culture of our country.

5. Throughout my nearly 13-year performance career, I gave up a great deal to fulfill my life’s biggest dream. From saying no to social events to avoiding activities that had even the slightest risk of injury, traveling for 4 years away from the comfort of my friends and family, and avoiding foods that may add that extra pound of weight onto my body, I sacrificed much to enjoy what I still consider one of the greatest experiences of my life. Now that I am officially retired from the stage, I have been able to enjoy my time in different ways. I now see that there is so much more to life than dance. But that doesn’t mean I love it any less. It is still the focal point of much of my attention. But I don’t limit myself in ways that I used to and I don’t feel like I am missing out as much.

6. While there is often a great deal of competition and comparison throughout a performance career, all former professional dancers share a special bond that connects them once offstage. One of my favorite experiences in recent history came while teaching a master class at Uptown Dance Company in Houston, TX when a former colleague with Houston Ballet took my class. She had been a long-time soloist with the company when I joined as a young apprentice and I looked up to her and respected her time put in. Since I was younger, I remember feeling shy around her. But now that we are both retired and have shared similar career experiences, we shared some good conversation and laughs while reminiscing about our past career lives.

7. When you retire, some aches and pains go away and other aches and pains get worse (The ones that get worse are usually when you are teaching – see previous blog post about this here). But the stress and anxiety that accompanies minor to moderate pain or injury is not nearly as great as when you are preparing to perform.

8. When I was finishing up my career in my early 30’s, I was often considered older for a dancer. By my late 20’s, I already found myself a guiding force for younger dancers entering the field. In fact, at one gig, I was jokingly referred to as Papa Bear. When I finally decided to officially retire at the age of 32, I suddenly became young again. I can’t tell you how many people have mentioned how young I am for a teacher and choreographer at my level, even at the age of 34. It was quite surprising to see how quickly I went from being old to young again. Perhaps, retirement from a performance career is the real fountain of youth.

9. Dancers are the face of our field. But as I have started to experience how I am treated (whether locally or traveling) as a choreographer and dance educator, I have come to see how absolutely undervalued and mistreated dancers are. When I freelanced around the country as a performer, I had to fiercely negotiate a livable wage, deal with questionable housing accommodations, and handle situations in and out of the studio that most professionals in other fields would never find themselves in. Since I have begun working in my post-performance career, I have been treated much more respectfully when it comes to salary, travel, accommodations, and treatment. This is definitely something that I would like to inspire to change in our field. I am still baffled that dancers, the face of our art form, are so often the least valued commodity in dance.

10. I’m actually more in love with dance than I have ever been. I thought that getting to perform my dream roles in my dream companies would be the pinnacle of my love for the art form. But while those experiences were amazing, there was a certain level of stress and anxiety that went hand-in-hand with preparation activities and live performance. Now that I have succeeded in my performance career and have moved on to teach and choreograph, I get to enjoy every part of the dance world that I love, leave the parts that I don’t love behind, and make sure that almost everything I do is for me, because I want to do it, and to share my passion with others.

As professional artists, we have worked very hard to perfect our art. In fact, for many of us, our entire lives have been dedicated to perfectionist acts in order to understand, live, and share our art form. For me, it sometimes feels like there is nothing more important than the refinement process in the studio, the artistic process in the psyche, and the exploratory process in the form of play, trial, and error. But at times, I catch myself sharing my artistic practices (something I care about very deeply) as if they have more value than anything else in the world. I’ve wondered over the years whether this makes me impassioned or gives off an air of pretension.

During my time dancing with Pacific Northwest Ballet, I was extremely unaware of the insular artistic bubble that I existed in. While dancing for this high-end organization for 7 seasons, dozens of highly qualified artists worked diligently daily beside one another using collaboration and competition to boost one another to the next level of perfectionism. This works well on an insular level. But it also tends to dissolve an artist’s reality outside of this bubble, as it requires an intense level of commitment and effort. Striving for perfection daily along with constant peer-to-peer comparison creates an atmosphere of exponential growth. But it also cultivates a sense of judgment that (while helpful and understood within our tight-knit community) bled outside of our thickly insulated bubble. This often led to intense scrutiny of all things across our art form as if they were all being judged by the same standards as we were, albeit not sharing our company history or budget. It took me leaving this intense, safe atmosphere to recognize the benefits and downfalls of having a mentality that the work we were doing was more important than most anything else. This was a place where anybody who wasn’t achieving an equally high standard as we were could be judged using words including bad, fat, unmusical, cheap, awful, weak, unqualified, and a variety of other negative descriptions. While this may appear as perfectionist behavior within one community, it may project as pretentious if these unwelcome opinions are shared.

Every dance artist has to start somewhere. Aside from maybe one or two prodigies in every generation that passes by, practically no dancer naturally begins performing technical exercises with perfection, maintains perfect physical form at all times, dances with immaculate musicality, or exudes the inner soul of every character they portray. Most of us start out with recreational intentions. And many of us do so without regards to how our feet are pointed, how fit we are, or how it makes us feel emotionally. All of these characteristics plus passion must be cultivated within an artist over a period of time without judgment beyond constructive individualized criticism. Similarly, all audiences must be shown why it is important for them to be involved in any cultural institution. If we present artists with expectations of pure perfection before they are ready to put that pressure upon themselves, it will be impossible to build the future of our art form.

In my own personal practice as a dance educator and choreographer, I have found myself exploring the practice of making our art form important to my students without coming off as pretentious about the need for extreme effort, motivation, and artistry. Just because I had success in my performance career and love what I do doesn’t mean that anybody who enters my classroom will share the same sentiment as me. Just because I tell a student that something is important doesn’t mean it actually is to them. What I try to do is slowly educate those in my classes about all aspects of our art form. By adding interesting trivia questions at the beginning of class, I subtly educate students on American (and sometimes international) dance culture. Whether listing off major, regional, and civic dance companies, to explaining the company rankings, offering details on full length and one act works, the internal administrative and artistic workings of a company, and choreographers of note, I offer information that a student can take home with them and research if they find it interesting. Beyond this, I use other tactics to motivate physical and artistic development. Only when we pique a blossoming artist’s interest can dance become something more than an after-school activity.

When I first started teaching, I expected dancers to work hard because I already had them in my classroom. What I found was that many dancers didn’t understand why they had to work hard or know how to work hard in a way that was effective. My perfectionist tendencies would project onto students and come off as pretentious because they had not yet bought into the process or the need to create a sense of importance around their work in the studio. It is necessary to buy-in to do many tasks that artists do. Why do I care that I am holding my leg at or above 90 degrees for 8 counts? Why does it matter if I do or don’t let my standing leg give out in a pirouette. Lately, I have found myself telling students that, in the grand scheme of the world, it isn’t important that they want to do these things. But in order to accomplish these feats, it is integral that in those moments they are working in class or onstage that they feel that the work is the most important thing on earth. Only then can we accomplish superhuman feats. But it is also important while working with impressionable students (young to senior) that we remind them that there is a reality outside of our beautiful art form that must be recognized.

Looking at the separation between pretension and perfection in our art form also lies in who we are interacting with and how we respond to others that we feel haven’t yet obtained the same level of execution or understanding that we have. If something is important to me, but not you, and I really push the point, I may come off as pretentious. We too often share the tendency to tear down others in their process of finding artistic excellence, especially without consideration for where they came from and where they are going. I remember when I first started my 4 years freelancing with multiple established and fledgling professional organizations across the country. Only having the standards that surrounded me during my time dancing at PNB, I judgmentally felt that anything that wasn’t on the level of work that I had been a part of during my tenure there was either bad, dysfunctional, or laughable. I was afraid to share some of what I was doing publicly for fear of humiliation when viewed through the eyes of my former colleagues. But what I learned throughout this period was one of the most important lessons I’ve learned throughout the entirety of my nearly 16 year career, thus far. We must remember that we are not all dancing along parallel tracks of artistic growth and expectation. We all exist in different stages of our art form and all have different purposes that can grow or reroute at any time. A great example of this can be seen in the differences between dance organizations across the country. Some regional dance companies are still in the audience education period of their organization’s growth. Yes, their practices may currently be flawed. Yes, the quality of their performances may pale in comparison to companies with multi-million dollar budgets. But most of the nation’s finest cultural institutions started this way. Look at American Ballet Theatre. When they were merely just Ballet Theatre touring around the country by bus and performing in any and every theatre possible, they probably didn’t have the finest quality productions. Additionally, there was no nationwide comparison to vouch for the quality of these dancers. But look at them today. They are one of the leading arts organizations in the world.

The important thing to recognize here is that all artists are an important part of our community, whatever stage they are at in our art form. And in order to continue cultivating dance into a sustainable place, we must develop the importance of perfectionist actions through a carefully curated process that neither pushes potential artists away from the art form, nor tears down working artists that are not quite as far down their professional path as you are. If a young dancer stops training because the teacher doesn’t slowly allow them to explore why our art form is important, we have failed. If younger arts organizations try to force their audience to understand our art form too quickly, people will look at the organization as if they are pretentious and the company may begin to lose support. Without community support an arts organization can no longer exist. Pretension is a turn off that slows down or completely halts the progress of our art. For this reason, it is so important that we don’t let our own personal or “insular-bubble” perfectionism project unto others. Instead, I find it best to offer a helping hand that is ready to offer guidance and insight only when an artist is ready to accept it.

As professional athletic artists, we come to expect to be in some sort of minor or major pain for a majority of our performance careers. Whether these aches are caused by day to day muscle fatigue or a more acute injury that requires rest, recovery, and healing, we are educated from early on in our training that these issues are a common hazard for dancers. I remember moments throughout my career where I dreamt of the days after I retire from the stage (of course, I hoped this would be after a prestigious performance career) and imagined myself guiding students through the rigors of professional track training free of pain and worry. Well, this day dream clearly wasn’t a reality because one of the biggest lessons I have learned in the early stages of my career as a dance educator is that teaching hurts!

Every one of us who has built our technique to a professional level knows how strenuous dance training can be. But what many instructors don’t realize is that, while not completely the same as a student in class, teaching is also taxing on the body. I have a particularly unique perspective here since I teach both ballet and contemporary technique classes to students ranging from recreational to professional. While there is a different approach to teaching each of these distinct styles of dance and level of students, I have found that I am in pain and at risk of injury just as much, if not more, than I was throughout my performance career. Why is this?

Being a younger instructor, I can still perform most of class at a high level. Even teachers who have been out of their performance careers for some time know how to fully execute the entire range of dance vocabulary and can still perform exercises with aplomb. Often, in our efforts to demonstrate for students, we forget that we weren’t warm to start with, we were warm and aren’t anymore (which is common when teaching multiple classes in a row), or we are constantly showing exercises on one side of our bodies (creating fatigue and imbalance in our muscles). It may not seem like a big deal when you are giving a plié or tendu exercise. But as we move to more extensive parts of class that include higher extensions or batterie, petite allegro, and grand allegro, we are likely to forget that we aren’t properly prepared to execute these steps. Giving class often tricks our mind into thinking that we are taking class because we go through the same pattern we did every day as a kid, teen, and professional. Only we aren’t performing these combinations beyond showing them to students. And in a moment where we are trying to convey the appropriate execution of a step to a student, we may forget that our ankles, legs, hips, and backs are not properly warmed up to show and share our physical knowledge.

While not always possible (some days I teach first thing in the morning), I endeavor to take morning class or to arrive early and give myself a barre before I teach. I have found that this helps me in the same way that warming up did when I was preparing for rehearsals or the stage. Sometimes, in my company life, I wouldn’t have rehearsal the first few hours of the day. But as long as I took class in the morning, my body only required a very short half barre to feel good enough to work through rehearsals. I find this helps greatly.

While this approach is generally helpful for my ballet classes, I am still navigating a safe approach when teaching contemporary technique. I have found that I am more at risk here due to the nature and structure of these types of classes. Over the past year and a half, I have been developing a codified contemporary training syllabus that is excitingly gaining traction. Where my classes first mimicked the format of a master class (warm up, technique exercises, choreography combo), they have grown into codified steps that can be strung together into combinations in the same way a ballet class does. Since I am currently the only one that knows these exercises (hopefully not for long), the movement is foreign to most people. In order to effectively teach certain movements, it is necessary for me to show steps full-out for much of class. With contemporary movement tending to be more off-center and less upright, it can really take a toll on one’s body. While I warm up earlier in the day for ballet classes with ballet, I need to be extra warm for contemporary classes right as they start. Unfortunately, my schedule rarely allots me this luxury. So, this is still a work in progress. While I prefer to walk around and correct my students, sometimes I find it necessary to join in performing exercises to make sure I am getting warm and staying warm. It is a tricky line to walk to ensure that my students are getting the most out of my classes and making sure I am warm enough to protect my instrument. One step I hope to take in the near future to counter stresses put on my body as a contemporary instructor is to cultivate enough dancers who know my technique to offer opportunities for students to assist in my classes. This will help me train dancers without risking injury and hopefully increase the longevity of my career.

One major commonality I have noticed among my colleagues is that teachers tend not to take care of pain and injuries in the same way that performers do. While dancing for Pacific Northwest Ballet, I had access to world class physical therapy, had regular massages, and addressed even minor aches and pains at onset of symptoms. Under the assumption that my teaching career would be easier on my body, I didn’t really head to the front of the studio with a game plan on taking care of myself. I remember the first time I spent more than an hour and a half at the front of the studio. I came home in shock, awe, and OW that I was so physically and emotionally exhausted. But this experience didn’t lead to an immediate sense of what my body required to continue teaching pain-free. Just like many dancers working professionally, it took my first real injury as a teacher to really raise my awareness and to take better care of my body.

While I am still not as good at taking care of my physical self as I would like to be, I see a chiropractor almost weekly, I am seeking a physical therapist I can reach out to without having to go through my doctor, and I try to get massages here and there. Of course, there is always the burden of affordability and financial stability. But as I move deeper into my career as a dance educator, I see how important it is to have a game plan and figure this out. It was really eye opening for me to realize what my teachers had gone through to pass on our incredible art form to me. And I am learning that if I want to do the same, that I have to be sure to take care of myself to ensure longevity in this second stage of my career.

(How do you take care of yourself in and out of the studio? Feel free to leave your answer in the comments)

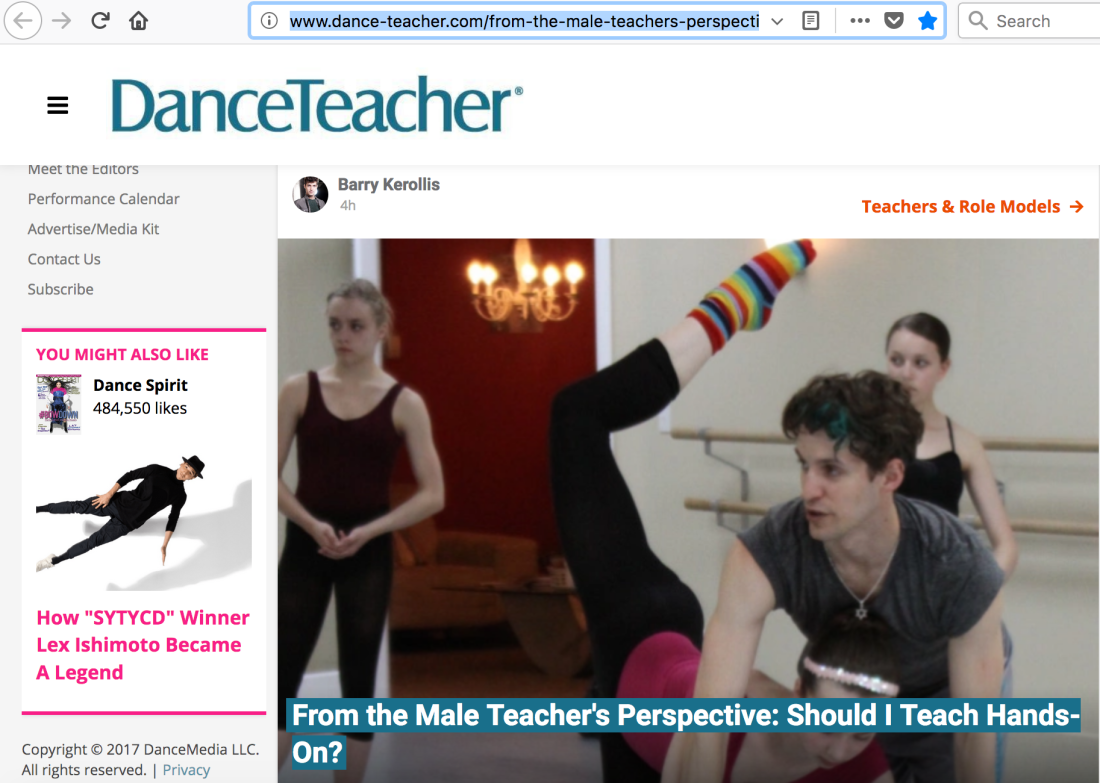

I hope that all of you lovely readers have had a wonderful holiday season and are eagerly awaiting what will hopefully be an amazing 2018. If you haven’t seen yet, Dancing Offstage has already been getting some exciting recognition, even in the infancy of this new platform featuring information on the post-performance careers of professional dancers. After writing my most recent post discussing whether I should perform physical corrections on students, I was contacted by Dance Teacher magazine to see if they could gain permission to share my writing on their website. I was honored to be published by this magazine, which marks the 2nd time my writing has been published by a dance periodical this year (check out my feature from Dance Magazine in May here). It has been on my goal list for a few years now to write for and be featured by a major dance publication, and it happened twice this year. Exciting times here at Dancing Offstage.

My intention in sharing this exciting news is not really to gloat (though I do hope it garners excitement and new subscribers). But instead it is the perfect segue to discuss goals, particularly goals that we often have as artists. And with the new year upon us, it seems an appropriate conversation. I’ve never really been one for resolutions. I honestly can’t remember the last time that I even set a resolution. This is mostly because I despise the idea of doing something because everybody else in society around me is doing it. Perhaps, this is the plight of an artist. I tend to write down my own personal goals as a part of a quarterly retreat that I try to execute in order to remain focused on reaching my wildest dreams (tune into last week’s podcast to hear my current goals). My major problem with resolutions outside of the general pack mentality in setting them as the earth prepares to restart it’s annual journey around the sun is that more people are setting themselves up to fail than laying the groundwork for the long, effortful process it takes to become successful. But, alas, people continue to be resolute as December’s holiday glow fades into January, a month that probably needs more inspiration than most.

Even though I rarely did it, I found that it was much easier to consider resolutions when I was in my performance career. I want to dance the role of Puck in Balanchine’s A Midsummer Nights Dream. I want to take better care of my body (less partying, more cross training). I want to be promoted to Soloist. As I continue to dig deeper into my career as a choreographer, dance educator, and media personality, I find that it is almost impossible to be resolutionary about my career. But at the same time, I find this strange pull to be both revelationary and revolutionary (Note: I’m pretty sure that I made up at least 2 words).

There was a period at the beginning of my dance career where I thought that I wanted to be famous. That time has long passed. But when my mom asked me if I still wanted to be famous a few years ago, I came to realize that my great ambition for achievement and success was driven by two things that had nothing to do with fame. First and foremost, my want and need to remain in the dance world post-retirement from the stage was the major driving factor for the work ethic I did and do maintain. I don’t want to live as a starving artist and I don’t want to burn out on my art form (commonly caused by struggling to maintain a quality adult lifestyle while gaining a certain compensation level in an undervalued and underpaid art form). Those artists who achieve the most onstage practically get handed jobs in our field the moment they step offstage. This is why I was so adamant that I needed to dance with a major company and keep an eye on my promotion outlook. If you take an honest view at the list of most retired leading dancers with American Ballet Theatre or New York City Ballet and see where they landed after they stepped offstage and how quickly that happened, you will see exactly what I am talking about. Many of them even land jobs as directors, shockingly, without any business or leadership experience other than dancing company repertoire and schmoozing with high level donors. My second reason for being so aggressively ambitious in building my portfolio has been due to the fact that I want my legacy to be that I contributed a great amount to our art form and that I shared a valuable wealth of information with our field. In other words, I aspire to inspire as a revolutionary. And as a part of the process of getting there, I hope to be revelationary.

So, here is the problem with this. I feel that every artist feels this nagging gravitational pull towards being somewhat revolutionary in their art. This is much more difficult as a stage artist who isn’t performing their own work. Dancers are the blank canvas that choreographers wish to paint on. The paint shouldn’t be put on the paper as the color green, yet reveal itself as blue when a passerby pauses to view the work. But once many of us move on to the afterlife of our performance careers, we have more freedom to make decisions. And that often makes us feel like we have to do something that hasn’t been done before (which is practically impossible) or we have to be so utterly unique that when we show our work the audience has an extreme reaction. There is such a gravitational draw with this that many of us feel we have to be more eccentric as artists. But is this really necessary?

When there is very little room left to be revolutionary, attempting to be radically innovative may come off as pretentious or cheap. There is something about trying so hard to be new or different that it destroys the character of the art and it lessens other’s opinions of the maker. This is where I think that it is more important to be revelationary. When almost everything original has been created, one must reveal the layers of their work that have not yet been as deeply explored. Nearly all of the best choreographers today are not creating revolutionary work. Instead they are revealing aspects of their art to audiences that have not yet been explored deeply or that were once brought to light and had moved into the realm of passé. Resolving for revolution is a dangerous act. Yet, it is sought by artists more often than revelation.

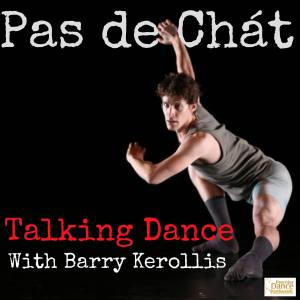

As I move forward into 2018 and continue building the foundation towards reaching three of my major goals, I find that there is no point in making a resolution to achieve these items. Instead, I choose to continue to take all of the small, medium, and large steps that I feel are necessary in order to continue making positive forward progress to achieve these goals. In the vein of revolution, I continue to seek information on an international scale to continue building and codifying my contemporary dance training program for pre-professional ballet dancers. Through this effort, I hope to gain a fellowship at NYU’s Center for Ballet in the Arts to provide additional support and network to achieve this. In the vein of revelation, I hope to gain the status of Permanent Faculty at Steps on Broadway and Broadway Dance Center (I am currently Guest Faculty in the ballet and contemporary dance departments with both of these organizations). I am fully invested in the concept that it is not so much the responsibility of a dance educator to tell a dancer what they need to do. But, instead, it is our purpose to reveal a dancer’s fullest potential to themselves in order to give them the tools, knowledge, and confidence to perform superhuman feats with the soul of an artist. And in the vein of revolution and revelation working concurrently, I hope to continue building my choreographic portfolio to include moderate to large scale regional and national organizations for main stage productions and to continue sharing my voice in our oft silent art form here and on my Pas de Chát: Talking Dance podcast. Happy New Year and Merde for a fantastic 2018.

(Will you be making any resolutions for 2018? Do you plan on being resolutionary, revelationary, or revolutionary?)

I was probably about 15 years old when this conversation occurred. It happened around the time I became extremely serious about the prospect of having a dance career. The director of my local dance school, seeing my drive and ambition, asked me to work as a teaching assistant for one of the main ballet instructors. She had asked to meet with me to discuss the details of my new job. Initially, she explained what my role was in the studio, expectations of me in the position, and more. But as we approached the end of my meeting, I wasn’t expecting the conversation to take the serious turn that it did. “Now, Barry, I need you to be very, very careful about how you work with these young girls. Kids are sensitive and, especially considering that you are a man, if you correct them in a way that can be viewed as sexual by either a student or a parent, even if you didn’t do anything, you could be jeopardizing your future as a teacher and in this field.” The look on my face must have been utter shock, as the prospect of losing my job or getting sued over sharing my art form had never crossed my mind. This forever changed my perspective on being a dance educator and I still find myself overly cautious about the way that I work with my students today.

Unless you’ve been hiding underneath a holiday blanket, it has become abundantly clear that we are undergoing a massive cultural shift here in the grand ole U.S. of A. It started in the entertainment industry, then shifted to major corporations. Sexual misconduct in the form of harassment and assault that had been swept under the rug for years began to bubble to the surface. Things began to boil quite quickly and those interested in our performing arts world were beginning to speculate if something was going to be brought up in our tight-knit community, especially considering the hands-on approach that teachers have with students, dancers have with other dancers, and artistic staff has while coaching employees. I had to sit on my own hands for over a month as I was given a heads up that a major news publication was working on an exposé about Peter Martins and his many abuses (which had been quietly circulating around our dance community for years). While the subsequent investigation into Mr. Martins’ behavior has yet to be complete, this has reignited my childhood concern about misinterpretation of touch in a class or rehearsal setting.

I’ve struggled throughout the entirety of my career as a dance educator with the decision on whether I should be a hands-on teacher or not. Dance is essentially the art of ultimate control of one’s own body. Understanding how to use your body correctly could mean the difference between an amazing feat or a debilitating injury. For example, proper execution as a student lifts their leg in adagio could result in greater height, better line, and exaggerated lift in the working leg. But more important than how it looks, a student who is not properly supporting and lifting their leg at superhuman heights can cause bulky muscles, seizing cramps, painful hip tendonitis, or worse. Sometimes, a teacher has to put their hands on a student to show them what their body should feel like when they aren’t properly aligned or are supporting themselves incorrectly. I know for a fact that this is effective. And I look back fondly on my teachers who were willing to get hands-on to show me how to work properly and assist me on my path towards my performance career. For this reason, I have made the decision to be one of those teachers that shares a very hands-on approach to teaching. Though, to be completely honest with you, I’m frightened by the idea of a poorly placed correction or an extremely sensitive student misinterpreting the intended purpose of physical adjustment.

I feel that this item isn’t as much of an issue for female teachers (though, I do know for a fact that they also have to deal with concerns about physically touching students for corrections) because of a few sensationalized cases of inappropriate teacher/student contact, which historically have been committed by males. In fact, there was recently a guest instructor who was arrested on the premises of a well-known New York dance school for sexually assaulting an underage boy at another one of his jobs. I was shocked to hear about this just as much as anybody else, especially considering that he hired me to teach master classes at his school in the past. But what was most disappointing for me here was that it gave dance parents fresh reason to be concerned that their kid’s teachers could act inappropriately towards their young ones. It is easy for protective parents to focus on one negative story. But for the few stories that have ever come out about these unfortunate circumstances, there are millions of positive experiences that students have with their teachers every day. It is important that schools focus on this and cultivate a safe environment that also includes educating parents/families on what is happening inside their studios.

Since dance is the art form of controlling our own physicality, we require students to wear skin tight clothing that shows physical alignment and muscle movement. This uniform leaves eager to please, impressionable children and teens exposed in a way that wouldn’t be acceptable in many places outside of a dance studio. If a student’s school isn’t educating their student body and their respective families about what is happening in the studio, this could lead to a more sensitive environment that could potentially be harmful to a qualified teacher’s career. Every school that I work for must have a waiver that is signed by all parents explaining that physical touch is an integral part of the learning process of dance. I refuse to work for a school that doesn’t have this protective measure in place. Beyond this, it is important that schools have regular parent observation days. Allowing parents to take a step into the learning process can offer them a better perspective on why certain practices are necessary.

I feel that my hands-on approach has really helped push my teaching career forward at a faster rate, especially in my open classes at Broadway Dance Center and Steps on Broadway, where corrections are often less frequent than other educational settings. Like I said, I am still a bit nervous that a misplaced hand or a sensitive student could cause issues. But I have enforced a handful of practices that I hope will continue to protect me as I offer the best training I can in ballet and contemporary dance techniques. First and foremost, whether I am giving a private lesson or conducting a large master class, if there are no windows into the studio, I will try to keep the door open. I have nothing to hide, so I feel that an open door policy allows anybody to view the classroom/rehearsal process. From here, I try to fashion the touch in my physical corrections into the most obvious, non-sexual type of touch possible. If I am working with a group of students that are not used to my physical corrections, I will often ask the student before I adjust them, “Are you comfortable if I move your body to show you how to do it correctly?” This is often met with a positive response. Though, I am respectful if the student tells me no. When correcting, I adjust students with the sides of my hands or with my palm while my fingers are glued together like a spatula. Fingers tend to be more touchy-feely and can have misinterpreted intentions, so I try to avoid using my fingers as much as possible. If I do absolutely need to use my fingers, I will make sure they are rigid and avoid any inappropriate places. When a student requires corrections anywhere near any private area, I absolutely do not apply physical corrections. Instead, if it is a correction near or on the pelvis, I will show by pointing to myself. If it is close to the chest area, I will often pretend like there is an invisible string attached to their chest and imitate the act of pulling on the string to get them to shift their chest placement. If there is anything involving the rear-end, if it is along the sides of the hips or high enough like the gluteus medius, I will use the sides of my hands or a knuckle with my fingers tucked into my palm. The final protection that I enforce as a dance educator is that I will ABSOLUTELY NOT follow a student into a private place. If I need a student who is in the dressing room or in a bathroom, I will ask a parent or a peer to get them. This way there is never any question that I have been around a student in a private setting.

There is no better teacher than one who can build you up with confidence as they teach you our deftly difficult art form. It is pertinent that students receive information with clarity. I honestly don’t feel that anybody can become a professional dancer without any physical adjustments. Our American culture tends to be touch-sensitive, which can sometimes leave students feeling extremely cautious about any type of physical adjustment from teachers. I made the decision at the beginning of my teaching career that I would be one of those teachers that risk their livelihood to offer the best training to my students possible. And, it has worked thus far. But I would be lying if I didn’t say that I approach each and every classroom I teach with tentativeness and an ounce of fear that one of my well-intended corrections may be misinterpreted as the worst of intentions. What has your experience been with physically correcting your students? Do you do it or not? And, if so, how do you approach making these corrections and protecting yourself as a dance educator?