I’ve been struggling with my weight recently. Now, before I get angry tweets or confused looks, I am aware that I am not actually struggling with my weight. Yes, I could lose about 5 pounds and be happy to see my six-pack abs return. But in the grand scheme of things, I probably look fit to the general public and my doctor would likely tell me that I am in the lower range of healthy weights for men my height and age. Taking all of these things into consideration, there is one more important item to note. I am probably not the image of the person I see in the mirror and that has changed drastically since I retired from the stage and began focusing my energy on choreography and teaching.

Throughout my 13 year performance career, I was always quite confident about my body. Yes, like any human being, my weight fluctuates up and down a few pounds from week to week. And back then, it may have swung a bit more if I had an extended lay-off or was recovering from injury. But I never felt stressed by these fluctuations. I knew that I would soon be back in the studio dancing for 7 1/2 hours a day and the image of myself that I wanted others to see would return. I didn’t have body dysmorphia then. I knew what I looked like and trusted the reflection I saw in the mirror. My stress, confusion, and acute attention with my perceived body image wasn’t an immediate response to retirement, though. It was a gradual shift in mentality after a few events that grew into mistrust about the person I saw looking back at me in the mirror.

Weight is a constant topic among professional dancers. While some of those conversations are serious, more of them occur in jest. Perhaps, this is in response to the stresses of a job where the central product is one’s fitness and ability to control every ounce of their body. I can actually note two singular comments that began my distrust of my own perception of self.

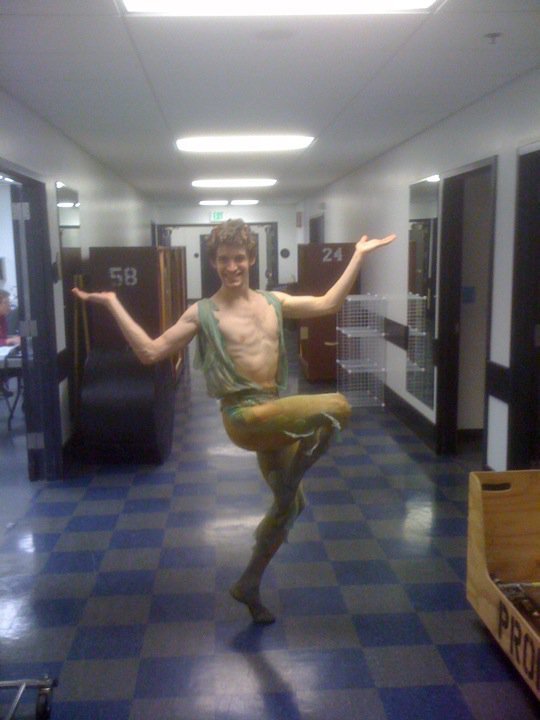

The first of these comments occurred as I prepared for the role of Puck in Balanchine’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. This role requires the dancer to wear a transparent, open-front vest attached to a glorified dance belt over swirly tights down to one’s ankles. The funny thing is that I didn’t even have this costume in mind as I prepared for the role. I had been heavier earlier in the season due to an injury that kept me out of the studio. So, it made sense that I lost that weight as the season dragged on. Also important to note, beyond my rehearsal days and performances that season, I was secretly flying on weekends auditioning to leave the company. All of this dancing and stress had taken a few extra pounds off me. It was after a particularly long weekend of travel that I found myself rehearsing with a Principal dancer who was playing the role of Oberon (the character who acts as my master in the work). While other dancers were rehearsing the part, this dancer pulled me aside and told me, “You look bone.” After I looked strangely at him, wondering if comparing me to a skeleton was a good thing or a bad thing, he must have caught the confusion in my eyes. He very quickly followed up by telling me it was a good thing. I looked in the mirror at my thin frame and sunken-in cheeks and smiled at the compliment. My lowest professional weight had now become my benchmark for physical success, sex appeal, and confidence.

Soon after this “compliment,” I moved on from Pacific Northwest Ballet, joined Ballet X, was let go from Ballet X, and started my life as a freelance dancer. With all of these changes and developments happening so abruptly, it took about a year after the bone comment before I had a moment to process all of the life changes I had experienced and allow my body to rest. It was also around this point that my freelance career began to take off and I careened on the wildest 4 year ride of my life.

One of the first stressors I noted during this period was that it was harder to stay in shape. I went from dancing 40 hours a week to rehearsing in bouts and taking expensive classes less frequently. Here, I began to see my strength, stamina, and weight fluctuate on a regular basis. If I was working a lot, friends would note that I was frighteningly skinny upon my return home. But after some time locally and not dancing due to extreme exhaustion, stress, and financial pressure, my weight would normalize or I would start to look a little soft around my torso. I controlled my frustration by telling myself that I needed the break, I would be working soon, or that it wasn’t as bad as I thought. I believed myself, even if I wasn’t at my lowest weight standard.

It took only one comment to destroy my ability to see an honest reflection of myself. My body dysmorphia was triggered during a guesting opportunity with Festival Ballet Providence. During this gig, I had befriended one of the dancers who was growing into the role of the company’s regular male lead. I hung out with him once or twice outside of work and had briefly met his boyfriend. After an open studio rehearsal that the dancer’s partner attended, he walked over to me and poked me in the stomach with his index finger. I still don’t understand why he felt this was appropriate. But after poking me, he stated that I was “looking a little soft.” While I tried to laugh it off, the stress I was experiencing in my new career style and the concerns I already had about my inconsistent work and how it affected my body sent me in a tizzy. Luckily, I’ve never been at risk for an eating disorder. But from this point forth, I’ve always been overwhelmingly conscious of my weight and how others view my current fitness versus how I looked at my lowest weight. The worst part of this unsolicited poke was that I lost the ability to reasonably judge my own reflection and the memory of what physical attributes made me feel happy and confident.

I handled this issue like I do with everything else. I stress about it and try to micromanage the situation, but have difficulty finding a perfect balance that makes me most comfortable in all areas. My body dysmorphia has only gotten worse since I retired from my performance career. It stressed me out to be dancing less throughout my freelance career. I’m sure one can imagine how it has gotten worse when I am in front of the studio more often than standing at the barre.

The biggest challenge as a retired dancer with body dysmorphia is cultivating an honest, healthy image of what I look like to myself and how I think I should look as a former dancer. Should I hold myself to the skeletal standard that garnered me positive attention during my performance career? Am I expected to have six-pack abs as a choreographer? And, if I don’t, will I lose my sex appeal or get comments about the loss of my “hot” body? I don’t have the answers to these questions. But I do know that it is important to consider a healthy image of myself as I age. In my 30’s, I still want to look like the person I was in my late 20’s. But it wouldn’t be fair for my 45 year old self to try and maintain the gold standard I had during my dancing days.

This post is more explorational than it is informational. I don’t yet have answers for retired dancers and how they should handle perception of their bodies after their prime athlete days. But what I can share is that I am working to understand how I view myself as I age, while appreciating that wonderful time when my body was fit just because I showed up to work. It would be unfair to always expect to look bone. So, now I need to explore what looks good on me at 34. And after I figure that out, I’ll probably have to reconsider that answer every 5-10 years. Just like the changes our bodies naturally endure as we age, we must also consider the mind.